Informatics - A Love Letter

“The objection that computing is not a science because it studies man-made objects (technologies) is a red herring. Computer science studies information processes both artificial and natural.” – Peter J. Denning (Denning, 2005)

For me personally, informatics is an empowering discipline - it is part of the emancipation of men. Its engineering quality can directly enable our fragile and limited body and mind. But its magic goes beyond practical use. Similar to mathematics, we discover its beauty in an abstract world. This Platonian world consists of fantastic, imaginative objects we can recognize, build and play with. In it, the problems of men are absent. There is no morality, no judgment, no conflict, no othering but harmony to enjoy, complex structures to discover, riddles to unravel, and logic-based creativity to get lost in.

Informatics is an Art

In popular culture, coding is often portrayed as something conspicuously ‘nerdy’ and alienating. A usually white ‘creepy’ man writes his code by typing seamlessly and rapidly into a black terminal. He never stops, he never interacts with other beings, and he never leaves his desk. Of course, everything works perfectly on the first try, and no one else seems to have any clue what’s going on. Intellectually, the programmer stands above everyone else; he is a genius, a mad scientist, or an introverted weirdo - only so important to do the necessary work and enable the ‘real’ hero. This toxic depiction of software developers (and introverted people) is wrong, dated, and was never accurate in the first place.

From the outside, coding looks like the most boring thing on Earth. This assessment is, of course, utterly wrong! Writing programs is a beautiful, creative and interactive process. To somebody who does it, it is the most exciting thing in the world. It is a game of chess but much more involving because you can make up your own rules and build your own world. Elementary entities accumulate to something bigger, something interconnected. The degree of freedom and creativity this process of creation offers can hardly be explained or understood if one never experienced it first-hand.

In no way does programming start in isolation at the computer, nor can we do it seamlessly. It is neither a strictly analytical nor a purely experimental process. Like writing an exciting story, it is a struggle, always! If it isn’t, we or someone else has already solved the puzzle - the exciting part has been gone. In that case, we do not create but translate.

One of the fascinating facts is that, in the end, everything comes down to simple symbol manipulations, which we call information processes. Software developers scoop, transform, and use information. They design data structures and algorithms like architects draw construction plans. Additionally, they have the power to build, combine, reuse and extend those objects of structured information. They command machines of blind obedience. The degree of control translates to a form of power and self-determination absent in the physical world. As Linus Torvalds rightfully noted:

“[Phyisics and computer science] are about how the world works at a rather fundamental level. The difference, of course, is that while in physics, you are supposed to figure out how the world is made up, in computer science, you create the world. Within the confines of the computer, you are the creator. You get ultimate control over everything that happens. If you are good enough, you can be God on a small scale.” – Linus Torvalds

In contrast to most other kinds of engineers, software developers can use a highly flexible and versatile resource. Information can be easily exchanged among peers, reshaped, conceptually described, and analyzed. In fact, it manipulates itself since any program is nothing more than well-structured information. Like many other materialized ideas, structured information arises from human thoughts; they result from a mental exercise. But the transformation of thoughts into objects of structured information is immediate. It is like writing a poem. Therefore, it can be an entirely personal and connecting experience to read the code, i.e., thoughts, of someone else. Over time, one learns to appreciate good code - its structure, aesthetic, modularity, level of abstraction, simplicity, consistency, and elegance.

By learning different programming languages, one learns different perspectives. I love Python’s lists notation and that functions are first-class entities.

But I’m not too fond of the indent notation.

The success of a programming language is bound to its popularity. Do developers like it?

Is it joyful to write code? Learning different programming languages taught me something about our natural language: the language I use forms my thoughts.

If a statement can be efficiently and aesthetically pleasingly expressed in a certain way, programmers will choose that way.

And sometimes, they overuse it. Furthermore, programmers look at a problem and go through their catalog of elegant expressions to find the one that fits.

A programming language not only determines what we can express but also introduces a particular bias in how we will express it.

The same is true for our natural language.

This seems not like a revolutionary insight, but we forget this fact in our daily life.

A change in language might have a more significant impact on material changes than we think.

Furthermore, this also highlights a fundamental problem of the human condition: we need abstractions and standards to communicate with each other.

But by using abstractions, we distance ourselves from others.

If we look beyond the code, beyond ideas written down in text snippets, programs are written to be executed. And those programs can serve almost any domain. They control robots, harvest semantic information, control networks of devices, and simulate the natural world and other virtual worlds. They establish communication channels, send messages with the speed of light across the Earth, compose and play music, and constantly search for structures in a rapidly increasing cloud of data points.

However, in the end, functionality is second to being exciting or pretty. Even coding itself is secondary. Figuring out how things work is the real deal. Since everything is self-consistent and logical, you can go on and on and never stop exploring. It is an endless stream, too immense for one lifetime. And you are not even bound to some external logic; you can make up your own as long as it is consistent. This consistency is a bright contrast to the corporate, social, and political world - it’s like going home to a place where everything is comprehensible, a place where you can find some truth within the bounds of its rules.

Informatics is a Science

As a software engineer, I want to build large architectures that process information. I want to express myself through code. In the world of physical objects, we have to study the properties of certain materials and the laws of physics to guarantee that our buildings do not collapse and rockets behave as expected. But how can we specify and verify structured information? How can we even define what we can compute? What is computable? Is sorting cards equally hard as solving a Sudoku? Here we enter yet another world, a formal one!

Of course, those two worlds are never entirely separated. Formal methods and objects, like the Turing Machine, the Lambda Calculus, logic, grammars, and automata are the mathematical backbones of informatics. They are a particular kind of mathematically rigorous description of information manipulation (computation). By analyzing those objects, we get to the very fundamental and interesting questions. I was never hooked by the purpose of formal methods in software development (verification and specification). Instead, I found them intrinsically fascinating! It was just enough to discover these formal, therefore, clearly defined objects. Again, it is tough to explain this attraction.

You start with a set of unambiguous definitions: an alphabet, a word over an alphabet, a tuple of a set of states, a transition function, etc. And you begin to construct slightly more and more powerful objects while analyzing the properties of these objects. You always try to keep their power controllable. Their properties should stay computable - you enter the realm of constructivism. You begin to recognize the equivalence of objects from entirely different fields, such as logic and automata theory. And you form beautiful proofs about very abstract thus general statements of your formally constructed world.

At some point, you arrive at a formal model of any digital computer, that is, the Turing Machine. Since you now have this gift, this formal model, you can analyze it in a highly abstract way. You can define what a computer at least requires to be Turing-complete, i.e., to be a computer. You can define what computable means, and you can even measure how many steps it takes to solve a class of problems. You start analyzing the complexity of problems, such as sorting cards or solving a Sudoku.

For example, sorting cards (on a Turing-complete model) requires \(\mathcal{O}(n\log(n))\) steps, where \(n\) is the number of cards. And we know that we can not do better than that. Consequently, in the worst case, sorting cards requires always at least \(c \cdot n\log(n)\) steps where \(c\) is some constant independent of \(n\). Isn’t that captivating that we know this!

Then there is the still unanswered question if solving a Sudoku is as hard as checking a solution of it? We call this

\[\mathcal{NP} \stackrel{?}{=} \mathcal{P}\]problem. Of course, we ask again in the context of Turing Machines. Therefore, one might argue that this is not a scientific question because we ask for some property of some human-made machine. I strongly disagree! This machine is a mathematical object, and mathematics is the language of nature. To this day, Turing Machines are THE model for computation (Lambda Calculus is equivalent); a Turing Machine can simulate even quantum computers. If nature does compute, we might even study its basic principles! Doesn’t it feel harder to solve a Sudoku than to check its solution? Isn’t there a fundamental difference? Or isn’t finding a proof much harder than understanding it.

Finding a solution involves what we call creativity and intuition. But checking it is a rather automatable process. So if we reframe the question, we may ask about the complexity of creativity! Since hundreds of publications falsely claimed to have solved the question, it seems to require a lot of creativity to correctly grasp the complexity of creativity.

What a fascinating scientific question to tackle! We are in the realm of not natural science but similar to mathematics, a formal science.

Eventually, you encounter another significant problem: the Halting problem. It states that there will never be a program (definable as a Turing Machine) that can test for an arbitrary program that it halts. Understanding the theorem and its proof in-depth feels groundbreaking and infinitely satisfying. The proof is simple and beautiful if you understand how computers, i.e., Turing Machines, work. You can find a sketch of it in the appendix of this article.

The Evolution of Informatics

Roots of Informatics

It is kind of funny that historically, informatics first struggled for recognition on a global scale. In academia, this struggle has been gone. However, in the general public’s eye, the objective and research subject of the discipline is blurred, which still leads to confusion: yes, I am a computer scientist, but I won’t fix your computer or software bugs!

If we look into the history books, computer scientists had to fight to establish their field. The discipline emerged from certain branches such as electrical engineering, physics, and mathematics. In the 1960s, computer science comes into its own as a discipline. Georg Forsythe, a numerical analyst, coined the term. The first computer science department was formed at Purdue University in 1962. The first person to receive a PhD from a computer science department was Richard Wexelblat, at the University of Pennsylvania, in December 1965.

In Germany, informatics goes back to the Institute for Practical Mathematics (IPM) at the Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, founded around 1928. But it required time to establish the first informatics course in the Faculty of Electrical Engineering in Darmstadt. The first doctoral thesis was written in 1975, ten years later compared to the US. In my hometown, the first informatics course at the Technical University of Munich was offered in 1967 at the Department of Mathematics. In 1992, the Department of Informatics split up from the Department of Mathematics.

Informatics can still be regarded as relatively young compared to other well-established disciplines such as physics, chemistry, or psychology. Nonetheless, new fields split up from informatics, and they are all interlinked with one another. We have, for example,

- scientific computing,

- computational science,

- information theory,

- and linguistics,

and the list goes on. The problem of artificial intelligence (AI) brings informatics more and more in touch with the humanities such as

- philosophy,

- psychology,

- and neurosciences.

The Disappearance of ‘Classical’ Informatics?

Within the field of informatics, there are a lot of branches one can pursue, for example:

- formal methods and complexity theory

- programming languages and compilers

- design and analysis of algorithms and data structures

- parallel and distributed computation

- high-performance computation

- networks and communication

- intelligent systems

- operating systems

- cybersecurity

- databases

- data science

- computer graphics

- image processing

- modeling and simulation

- artificial intelligence

- software engineering

- architecture and organization

This sprawling list of specialties indicates no longer such thing as a classical computer scientist, right? Nobody can be an expert in all areas - it is just impossible! Over the years, some branches lost, and others gained attraction, but most are active. For example, we lost interest in operating systems but put more effort into investigating high-performance computation and data science. Theoretical informatics cooled down, but there are still many critical questions unanswered.

Despite this abundant variety, being a computer scientist is more than being an expert in one specific field. It is more than knowing how to build large software systems, manage networks, process data and establish a secure infrastructure. It is a way of thinking! And no, we do not think like computers but embrace the curiosity naturally given to us human beings. We renew the playing child within us and let it go wild to solve riddles for no particular reason. And I think that is one of the most human things to do.

A New Perspective on Information

In this little supplementary section, I want to talk about the resource we are working with: information.

As you may notice, I call computer science by the European term informatics. But not only because I am from Europe but also because the term leans more towards information instead of computation. Information manipulation is computation, but it emphasizes a more abstract broader definition of computation.

Information, as we understand it is the elimination of uncertainties but on a purely syntactical level. This notion dated back to 1948 and was defined by Claude E. Shannon in A Mathematical Theory of Communication:

“Frequently, the messages have meaning; that is, they refer to or are correlated according to some system with certain physical or conceptual entities. These semantic aspects of communication are irrelevant to the engineering problem. The significant aspect is that the actual message is one selected from a set of possible messages. The system has to be designed to operate for each possible selection, not just the one which will actually be chosen since this is unknown at the time of design.” – Claude E. Shannon (Shannon, 1948)

In the humanities, researchers have a completely different understanding of information. They discuss cognition, representations, referencing, and interpretation in the context of information. What does a symbol mean, and what effect or interpretation does it has? How does data transform into information, and how do we harvest knowledge and wisdom?

For the purpose of information transmitted via a technical channel, a purely syntactical perspective is appropriate. But it seems inappropriate if we discuss today’s information-driven society.

Nowadays, we can rapidly collect unimaginable amounts of information. It can be processed automatically and checked for higher-level patterns that would not be discernible without technology. We constantly transform information into a machine-readable format, which makes it, in turn, quantifiable. But is there information that is not machine-readable, and do we dismiss it?

Furthermore, the interconnected world of information processes of today never forgets anything. Incessantly, it sucks up data and floods our private and public spaces with it. It is like a magical beast that can create amazing miracles but can also cause devastating destructions - sometimes it appears as a lovely creature, and sometimes it embodies a frightening monster. We have to deal with it! It is our creation - an artificial intelligence that already evaluates, categorizes, interprets, and generates information on its own. It has to include the semantics of information. Otherwise, it would be difficult to call it artificial intelligence.

Since we left the task of pure information transformation a long time ago, we need the perspective of the humanities - we have to think beyond pure syntax. In fact, we have to reconsider the term information, at least in our discipline. For example, Ulrich states:

Where data are the raw facts of the world, information is then data ‘with meaning’. When ‘data’ acquires context-dependent meaning and relevance, it becomes information. Furthermore, we obviously expect information to represent valid knowledge on which users can rely for rational action. – W. Ulrich (Ulrich, 2001)

But even this definition seems problematic. Is there even something like simple brute facts of the world? All data seem to be already gathered and processed. Therefore, information can not simply be the injection of meaning into data because data already has meaning. It is more like the individual degree of significance differs. What might be meaningful to me might be utterly meaningless to you.

Of course, we can not answer this question of an adequate definition here. But to disregard it entirely and leave the design of interconnected information processes solely to the technicians would be a mistake. Discovering, studying, using, influencing, and extending our interconnected world of information processing, is exciting as well as necessary. It is part of our duties, but we should no longer encounter this beast alone.

Appendix

The Halting Problem

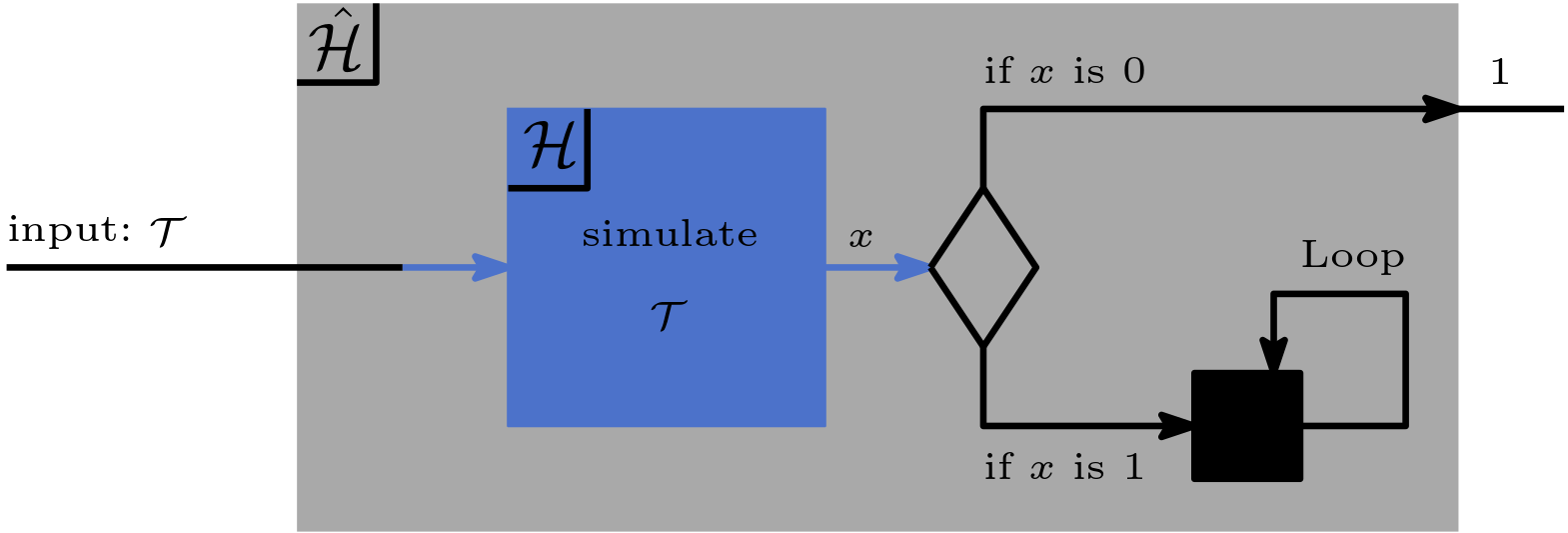

Let me try to give you the intuition of the Halting problem. For simplicity reasons, I will not explicitly distinguish between a Turing Machine \(\mathcal{T}\) and its description (often noted by \(\alpha_\mathcal{T}\)). So when a Turing Machine gets as input another Turing Machine, I mean its description (source code).

Proof

Let us assume there is a Turing Machine \(\mathcal{H}\) that takes an arbitrary Turing Machine \(\mathcal{T}\) as input. \(\mathcal{H}(\mathcal{T})\) outputs 1 if \(\mathcal{T}(\mathcal{T})\) halts, otherwise it outputs 0. So if such a program exists, \(\mathcal{H}\) is the program that solves the Halting problem, and \(\mathcal{T}\) is an arbitrary program. We can pick \(\mathcal{T}\) as its own input because the input can be arbitrary (but finite). So we ‘feed’ the program \(\mathcal{T}\) with itself, that is, its own description/source code \(\mathcal{T}\).

So we have

\[\begin{equation} \tag{1}\label{eq:halt:1} \mathcal{H}(\mathcal{T}) = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } \mathcal{T}(\mathcal{T}) \text{ halts} \\ 0, & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases} \end{equation}\]We construct a new Turing Machine \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\). \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\) is a slight modification of \(\mathcal{H}\). It does almost the opposite. \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\) halts and outputs 1 if and only if \(\mathcal{H}\) outputs 0. Furthermore, \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\) does not halt if \(\mathcal{H}\) outputs 1.

\[\begin{equation} \tag{2}\label{eq:halt:2} \hat{\mathcal{H}}(\mathcal{T}) = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } \mathcal{H}(\mathcal{T}) = 0 \\ \text{undefined, i.e., loops endlessly} & \text{if } \mathcal{H}(\mathcal{T}) = 1 \end{cases} \end{equation}\]

Now we execute \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\) by feeding it to itself, that is, \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}})\) and analyse the result:

It outputs 1: Let us assume \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}}) = 1\). Following Eq. \eqref{eq:halt:2} gives us \(\mathcal{H}(\hat{\mathcal{H}}) = 0\). But by following Eq. \eqref{eq:halt:1} this implies that \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}})\) does not halt. After all, \(\mathcal{H}\) outputs 0. Thus, it recognizes that the analyzed program \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\) does not halt. But if \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}})\) does not halt, it follows by Eq. \eqref{eq:halt:2} that \(\mathcal{H}(\hat{\mathcal{H}}) = 1\) which leads to a contradiction.

It outputs 0: Let us assume \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}}) = \text{undefined}\). \(\mathcal{H}(\hat{\mathcal{H}}) = 1\) follows from Eq. \eqref{eq:halt:2} which implies that \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}})\) does halts, compare Eq. \eqref{eq:halt:1}. But if \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}})\) halts then by following Eq. \eqref{eq:halt:2}, \(\mathcal{H}(\hat{\mathcal{H}}) = 0\) which leads to a contradiction.

In any case \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\hat{\mathcal{H}})\) leads to a paradox! However, the construction of \(\hat{\mathcal{H}}\) is correct if \(\mathcal{H}\) exists. Therefore, it follows that our assumption is wrong and \(\mathcal{H}\) can not exists!

Meaning

The Halting problem is strongly connected to the question of decidability. It asks if, for some problem or statement, an algorithm or a proof solves the problem in a finite number of steps or proves the statement. As we saw, the Halting problem is undecidable! Any Turing-complete machine or system is undecidable, and there are many such systems! For example:

- complex quantum systems,

- the Game of Life,

- airline ticketing systems

- the card game Magic,

- and, of course, almost any programming language is Turing-complete.

There are three essential properties for a desirable mathematical system, and we may think they are fulfilled naturally. But as it turns out, this is not the case. We would like to have a system that is

- complete: any statement of the system can be proven or disproven

- consistent: a statement can not be proven and disproven at the same time

- and decidable: an algorithm (proof) requires a finite number of steps to prove or disprove any statement

Kurt Gödel showed that any decently functional mathematical system is either incomplete or inconsistent. Later, he also showed that even if such a system is consistent, this can not be proven within the system. After Alan Turing found a computation model, the Turing Machine, he showed that

- many problems / systems are Turing-complete

- all those systems are undecidable.

This revelation crushed the mathematical landscape and ended the dream of David Hilbert and others to establish a solid mathematical foundation. Sadly, Kurt Gödel, as well as Alan Turing, one of the most brilliant minds, died tragically.

References

- Denning, P. J. (2005). Is computer science science? Commun. ACM, 48(4), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/1053291.1053309

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J., 27(3), 379–423.

- Ulrich, W. (2001). A philosophical staircase for information systems definition.