Laws of Form

In my last blog post, I discussed Niklas Luhmann’s Social Systems Theory and I emphasized that his theory is based on differentiation and seemingly paradox relations. My general understanding of Luhmann’s radical constructivism in the most reductive sense is that there are no unified and independent objects—there are only differences. What an observer can identify as an object is a differentiation of a system and its environment, a foreground and its background, an interior and the external. However, any observer is itself a distinction between system and environment. I want to further investigate this idea by looking into Luhmann’s inspiration—his muse so to say. So let me examine the logic of Georg Spencer-Brown presented in his work Laws of Form (Spencer-Brown, 1969).

The Principle of Differentiation

As mentioned, Luhmann’s theory is based on paradoxes such as

This statement is wrong.

The statement is logically problematic because it is self-referential. If the statement is false, it states that it is in fact true and if the statement is true, it states that it is false. Another famous paradox is Russell’s antinomy of the naïve set theory:

\[R := \left\{ x \ | \ x \not\in x \right\}.\]\(R\) is the set of all sets that do not contain themselves which seems to be a well-defined mathematical object. However, if we introduce the self-referential relation, we run into a paradox:

\begin{equation} R \in R \iff R \not\in R \end{equation}

This paradox is related to the barber that shaves everyone that does not shave themselves. If that is the case, does the barber shave themselves?

Another example involves the the proof of the Halting Problem. To prove it, one can establish a self-referential relation between a machine that presumable solves the Halting Problem. The machine does not halt if the machine it checks halts, and it halts if the machine it checks does not halt. Via the self-referential relation, that is, by letting the machine check itself, we get a contradiction.

The idea of Spencer-Brown is to resolve these paradoxes over time. \(R \in R\) holds at one moment in time and \(R \not\in R\) holds at the next moment. Note however that he does not resolve Russell’s antinomy (Cull & Frank, 1979). His idea of resolving paradoxes over time is reminiscent of the Hegelian dialectic—a process of self-creation. The self-referential relation is a paradox if we ignore time and it becomes a generator if we consider time and place.

This led the biologists Huberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela to the concept of autopoiesis (Maturana & Varela, 1987). Furthermore, the importance of differentiation is inspired by the logic of Spencer-Brown and his work Laws of Form (Spencer-Brown, 1969). He resolves the paradox by a similar idea that gave us imaginary numbers, that is, by using what he calls Re-entry which (re-)introduces a system into itself.

Luhmann integrated this idea into his social systems theory. For example, the media can observe and reintroduce itself into itself. It can use its systemic operations on itself, i.e. it can report on itself.

Spencer-Brown begins his work by a quote from Lao-Tse (a stand-in for many different authors) thus begins by philosophical considerations:

Wu ming tain di zhi shi. – Loa-Tse

The sentence has mainly two different meanings. One is:

The beginning of heaven and earth is without a name.

The other one is:

‘Nothing’ is the name of the beginning of heaven and earth.

A paradox arises: How can Nothing be nothing if we can call it ‘Nothing’? Furthermore, the quote points to a distinction between heaven and earth. Can there be heaven without earth—a calling or indication without a distinction? Spencer-Brown begins by the assumption that there is no such thing:

We take the idea of distinction and the idea of indication and that we cannot make an indication without making a distinction as given. Therefore, we take the form of distinction as the form itself. – Georg Spencer-Brown

In other words, what we normally identify as object (the form / system) is for Spencer-Brown equal to the distinction (system-environment differentiation). There is no clear separation between the object or the result of distinction and the process of distinguishing. Therefore, the process must be integrated into Spencer-Brown’s logic and as we will see, there is no clear separation between objects and operations in Spencer-Browns calculus. Spencer-Brown thinks that differentiation is a proto-operation that is more fundamental than performing calculations or writing text because to do these activities we have to differentiate beforehand. I cannot calculate 1 + 1 = 2 without distinguishing between the different symbols and a symbol and ‘nothing’ or the void.

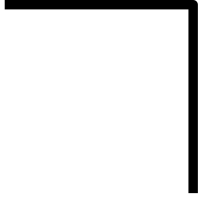

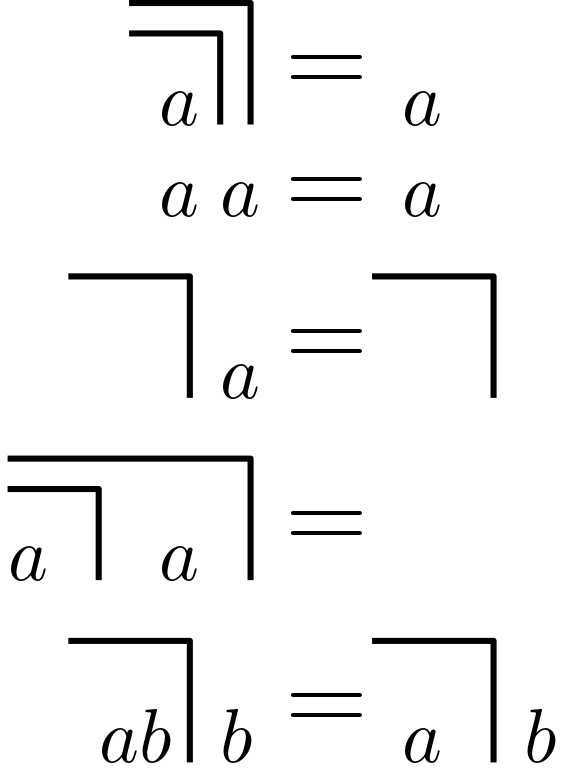

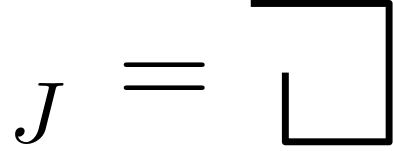

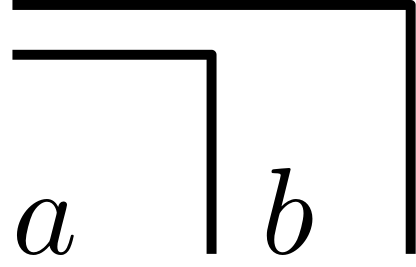

Spencer-Brown uses the mark or cross (result) which at the same time marks (process). The mark is, calls, and makes a difference.

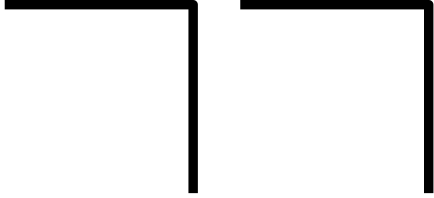

There is an interior of the mark and not the interior—the system and its environment. I can make a distinction again (repetition):

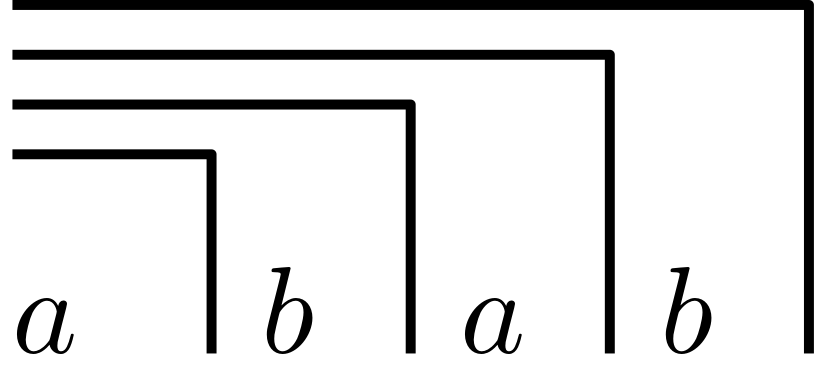

But making a distinction again does not change the distinction.

Calling something back-to-back by its name does not change its name. – Spencer-Brown

The reverse is also true; therefore, Spencer-Brown introduces the Law of Calling:

The second transformation called Law of Crossing is less intuitive. Crossing twice reverses the first crossing.

If a boundary is crossed twice, the original state will be reestablished. The repetition of the crossing has a different value than the single crossing. The reason is that in-between the reversal happens. Crossing changes the side. Re-crossing reverses this operation. – Spencer-Brown

With only these two laws, Spencer-Brown established a logic calculus and we can start doing mathematics. Interestingly, the Law of Crossing and the Law of Calling are implicitly established via the position of the marks. There is no operator introduced because the result and process, indication and differentiation, the mark and the process of marking are not separated.

Let’s see what we can do with this calculus. Let \(a, b\) variables, then the following holds:

Let’s have a look at the last transformation. Let us assume \(a\) is a mark. Then we get:

Let \(a\) be unmarked instead, then we can follow:

The Re-Entry

How can we re-introduce the system (here an equation) into itself? Or in other words: How does the re-entry work? We can start by a simple self-referential algebraic equation:

\begin{equation} x^2 = ax + b, \quad a, b \in \mathbb{R}. \end{equation}

This equation has well-known solutions. It is also known that solutions can be imaginary, i.e., \(x\) might be of the for \(r + si\) with \(r, s \in \mathbb{R}$ and $i^2 = -1\). To see the re-entry, we can rewrite the equation above to get

\begin{equation} x = a + b/x, \end{equation}

thus the self-reference is obvious and we solve the equation by the re-entry

\begin{equation} x = a + b/(a +b/(a+b/(a+b/a+b/(a + \ldots)))). \end{equation}

Using this infinite formalism it is literally the case that

\begin{equation} x = a + b/x, \end{equation} holds. Using the same formalism, we can define the imaginary number \(i = -1/i\) as literally

\begin{equation} i = -1 /(-1 /(-1 / (-1 / \ldots ))) \end{equation}

but what does this mean?

The system is not a number but a process, a generator that generates itself.

\(i\) alternates between 1 and -1.

Interestingly, this is precisely how we use the equal sign in most programming languages.

Writing i = i / -1 in a programming language means

\begin{equation} i \leftarrow \frac{i}{-1}. \end{equation}

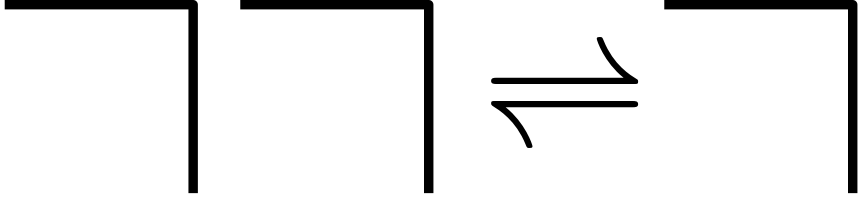

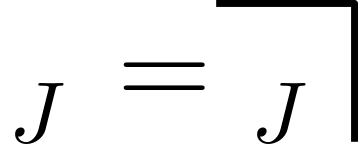

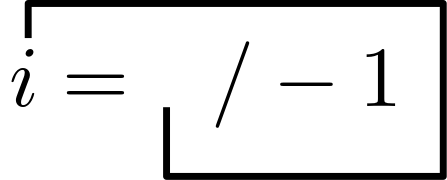

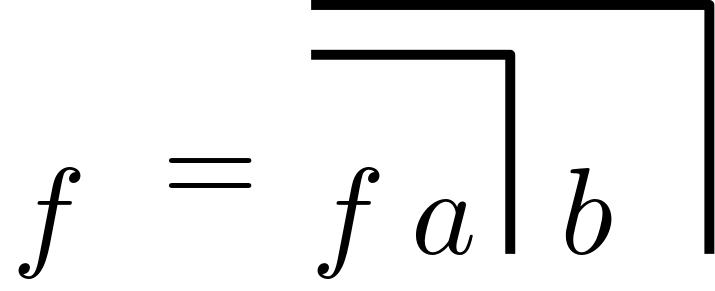

The next step is to introduce such a re-entry into logic. Similar to the imaginary number \(i\), Spencer-Brown gives us the following fundamental paradox (The Re-Entry of the Mark):

The solution is an alternation between a marked and unmarked state—between true and false. A state that might seem contradictory in space, makes sense if it is observed in time and space. Again, time resolves the paradox. To highlight the re-entry, Spencer-Brown also uses the following notation:

We could similarily notate \(i\) as

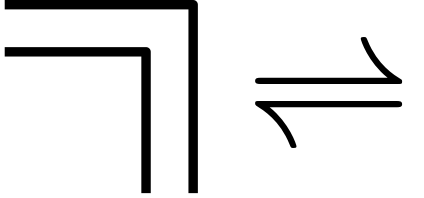

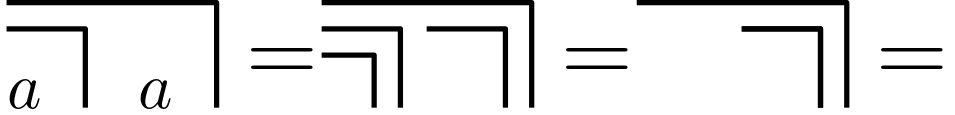

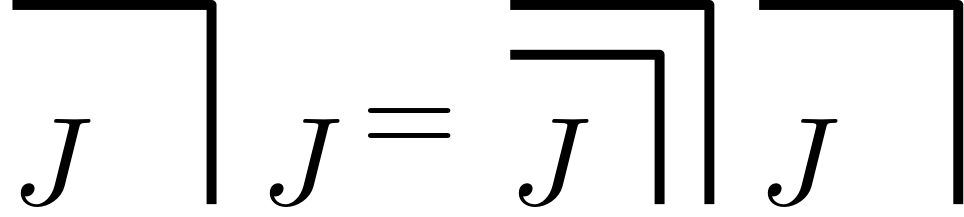

If we change all symbols within a system equally, there is no reason not to calculate with a self-generating process. For example, we can state the following:

However, it is forbidden to only change one appearance of \(J\)! Following this simple rule, no paradox or inconsistency arises. We can go on and evaluate the following transformation:

which describes two alternating waves shifted by one cycle resulting in a mark.

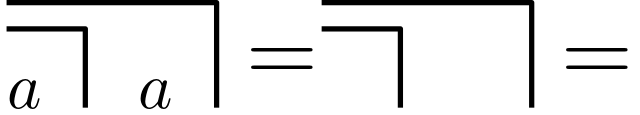

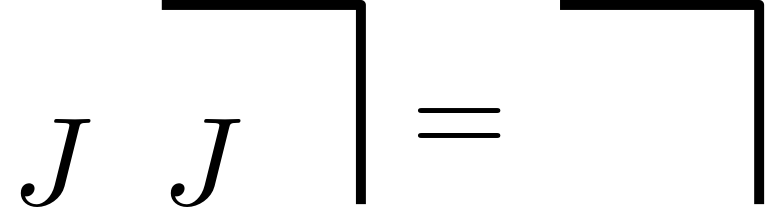

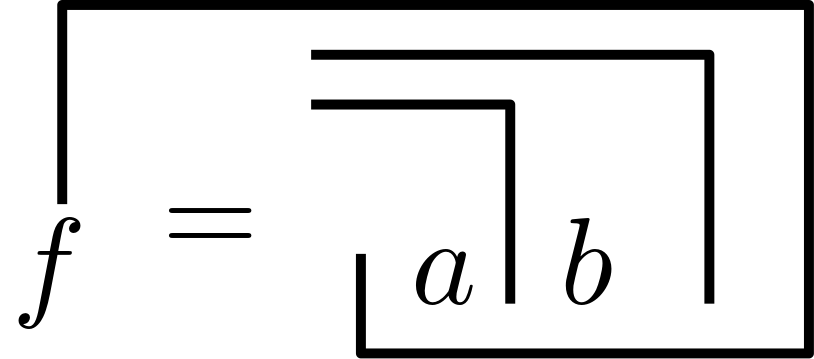

Spencer-Brown goes on and defines his Echelon:

which can be transformed into

thus gives us the re-entry

or

Final Words

In the act of programming there is no problem of using expressions such as

\begin{equation} i \leftarrow i + 1 \quad \text{ or } \quad a \leftarrow f(a) \end{equation}

but in mathematics—at least since Plato—we assume some sort of eternity. Of course, we can translate between the static world of “normal” mathematics and Spencer-Brown’s dynamic viewpoint, but it is a different viewpoint which might influence how we observe our environment. It is like in physics where multiple theories are equivalent but start from very different viewpoints. It starts by differentiation which gets reintroduced into the system which is constructed by this very same differentiation. To generate new numbers, such as irrational or transfinite numbers, Spencer-Brown proposes not to use the limit but the whole infinite process that defines such limit.

Spancer-Brown beliefed that to be able to master the transition to new signs, something is necessary for which the previous signs are not sufficient. To be able to close this gap; to make this leap successfully; to resolve paradoxes; a specific language of one’s own is necessary. According to Spancer-Brown this step is accomplished by thinking which provides us with its specific imaginations, playful freedom and contradictions.

It is surprising that Spencer-Brown’s Laws of Form plays no role in computer science even though it fits quite neatly in the perspective of programs, processes and computation.

References

- Spencer-Brown, G. (1969). Laws of Form. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Cull, P., & Frank, W. (1979). flaws of form. International Journal of General Systems, 5(4), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081077908547450

- Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The Tree of Knowledge. Shambhala.