Notes & Midi Notes#

While notes are introduced by musicians a long time ago, midi notes—a rather recent invention—became especially popular with the introduction of analog and digital synthesizers. Both are motivated and related to piano keys.

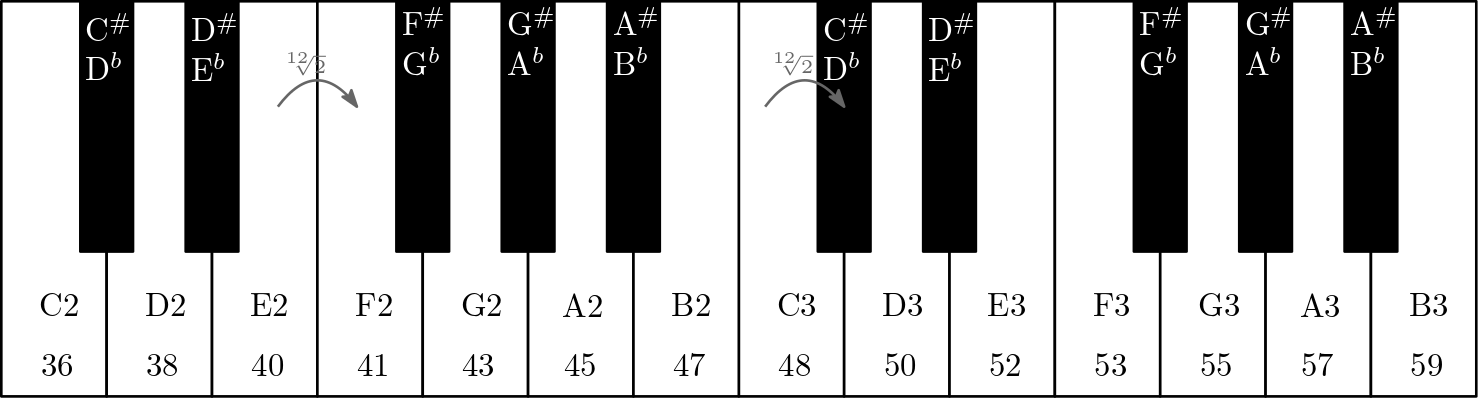

Fig. 72 Piano keys labeled by their note and corresponding midi note.#

Notes#

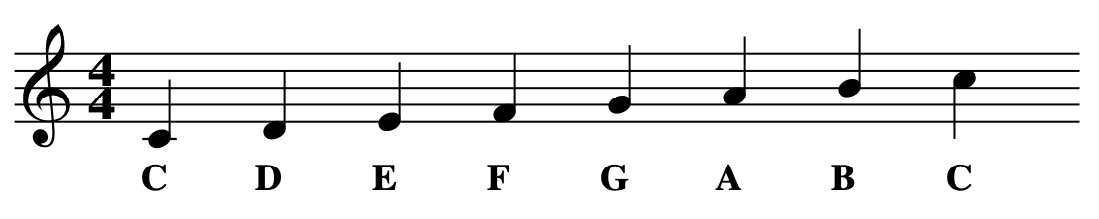

There are twelve piano keys within an octave. White keys are numbered with consecutive alphabetic letters A-B-C-D-E-F-G. But normally we start from C, that is, C-D-E-F-G-A-B.

Fig. 73 Notes written down on a musical sheet with a treble staff.#

Black keys are sharps and flats of the white keys: C#/Bb-D#/Eb-F#/Gb-G#/Ab-A#/Bb. To arrive at a black key we either raise a white key by a semitone, e.g. C to C#. Or we lower a white key by a semitone, e.g. E to Eb. All these letters represent a note. Often we notate sharps when we play in ascending order, e.g., C-D# and flats if we play in descending order, e.g., E-Db (instead of E-C#).

Modern pianos usually follow the twelve-tone equal temperament tuning (12-TET) thus after 12 notes in ascending or descending order, everything is repeated but one octave higher or lower respectively. Furthermore, A4 corresponds to a fundamental frequency of 440 Hz. A1 and A3 are the same note but A3 is two octaves higher thus its pitch is higher. We also say that they are in the same pitch class A. Additionally, the frequency of A3 is equal to the frequency of A1 multiplied by \(2^2 = 4\). In general, the frequency doubles after each succesive 12 keys.

Suppose we number all notes by natural numbers, e.g. F0 = 4, G0 = 5, A0 = 6, B0 = 7, and so on. Then to compute the fundamental frequency \(f(p+1)\) of the note number \(p+1\) given the frequency \(f(p)\) of the note number \(p\), we have to multiply \(f(p)\) by \(2^{\frac{1}{12}}\). In other words

Since there are the same number of keys for each octave but higher octaves cover a much larger range of frequencies, we can conclude that high frequencies are likely to appear much sparser in a piano piece.

Midi Notes#

Midi notes are just a numbering convention for piano keys. They were introduced with the musical instrument digital interface (MIDI) and realise a bijective mapping from a subset of natural numbers to piano keys.

The different piano keys are numbered in an ascending order from left to right. A higher midi note corresponds to a higher pitch. The note A0 corresponds to the midi note 21, B0 corresponds to the note 22 and A1 corresponds to 33. In general, the note A\(k\) corresponds to the midinote

because the key pattern of a piano repeats itself and each succesive 12 keys corresponds to one octave (see section Intervals). Consecutive piano keys have consecutive natural number as midi notes.

Using Eq. (94) and the fact that the midi note 69 corresponds to A4 which corresponds to 440 Hz, we can compute the fundamental frequency \(f(p)\) for a specific midi note \(p\) by the following function:

sclang has a build-in function to translate frequencies to midi notes and vice verca:

440.cpsmidi // 69.0 frequency to midi

60.midicps // 261.6255653006 midi to frequency

Conversion#

There are twelve piano keys within an octave are C, C#/Bb, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, G#/Ab, A, A#/Bb, B. This is equivalent to the chromatic sacle. The letter gives us the ptich class / tone while the number tells us in which octave we are. The combination determines the actual pitch.

Since any piano key corresponds to at least one note, there is a function that gives us a midi note for a given note, for the tuning of a piano. The following function computes the note for a given midi note.

(

// computes the note for a given midinote

~toNote = {

arg midinote;

var notes = [

'C', 'C# / Db', 'D',

'D# / Eb', 'E', 'F',

'F# / Gb', 'G', 'G# / Ab',

'A', 'A# / Bb', 'B'

];

notes[midinote % 12] ++ (midinote / 12 - 1).floor.asInteger;

};

// F4

~toNote.(65);

// [ F4, C5, G6, D7, A7, E7, B7 ]

Array.series(size: 7, start: 65, step: 7).collect({arg k; ~toNote.(k)});

)

In the last line I construct the keys of the C major scale using succesive intervals of perfect fifths, see section Intervals.