LTI Filters#

In the following I will discuss a special kind of filters, that is, linear time-invariant filters because almost all filters you will encounter in SuperCollider are based on this type of filters. It is recommended that you read section \(z\)-transform before continuing or that you go back and forth to understand the concept of a Z-transform.

What is a Filter?#

A digital filter refers to any electronic or digital system that enhances or reduces frequencies within a signal. Broadly speaking, any medium that a signal traverses, regardless of its form, can be considered a filter. However, an entity is typically not deemed a filter unless it has the ability to alter the signal in some manner.

For instance, while speaker wire is not classified as a filter, the speaker itself is, regrettably. The production of different vowel sounds in speech mainly involves altering the shape of the oral cavity, which modifies the resonances and consequently the filtering characteristics of the vocal tract. Devices such as reverberators, echo units, phase shifters, and speaker crossover networks serve as examples of beneficial filters, whereas the uneven amplification of certain frequencies in a space with poor acoustics illustrates unwanted filtering.

A digital filter operates on digital signals specifically. It involves a computational process that converts one numerical sequence, \(x[\cdot]\), into another, \(y[\cdot]\). Digital filters are capable of replicating the functions of physical filters with a high degree of accuracy. Therefore, a digital filter represents a method for transitioning between digital signals. It can manifest as a

theoretical equation,

a loop within computer software,

or a series of interconnected integrated circuit chips.

Why Learn About Filters?#

Computer musicians frequently incorporate digital filters into each piece of music they produce. For instance, achieving a rich, resonant sound from a computer is challenging without the use of digital reverberation. However, the potential of digital filters extends far beyond just reverberation. They can precisely tailor the sound spectrum to specific needs.

Despite this, only a handful of musicians are equipped to create the filters they require, even when they have a clear vision of the desired spectral alteration and this book aims to support sound designers by providing an overview of the most important filters implemented in SuperCollider.

Numerous software options exist for creating digital filters, suggesting that only basic programming skills might be necessary to utilize digital filters effectively. While this may hold true for straightforward tasks, a deeper understanding of how digital filters operate is beneficial at all stages of using such software.

Additionally, to adapt or customize a program, one must first thoroughly comprehend its workings. Even for standard uses, proficiently applying a filter design program demands knowledge of its design parameters, which is grounded in an understanding of filter theory. Importantly, for composers crafting their own sounds, mastering filter theory opens up a wide array of creative filtering possibilities that can significantly impact sound quality. From my own hands-on experience, a deep grasp of filter theory has been an invaluable asset in designing musical instruments. Often, the need arises for a simple yet unique filter, different from the conventional designs readily available through existing software.

An Impossible Filter#

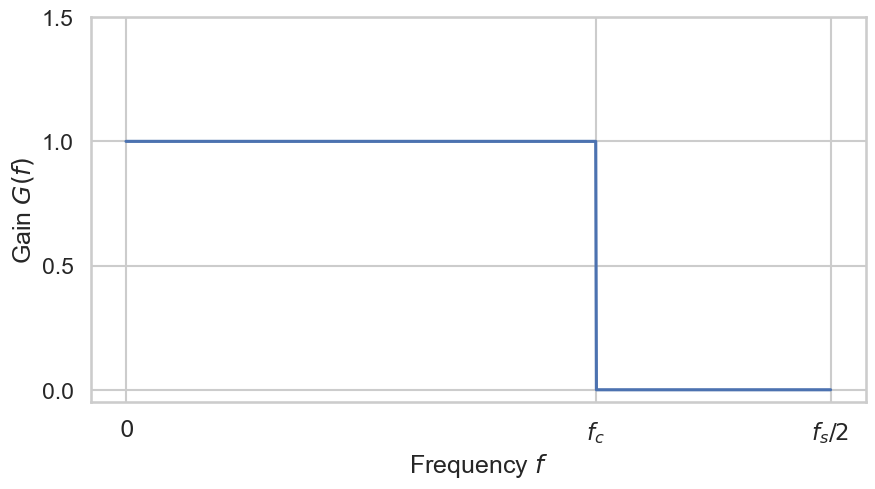

If we aim to entirely filter out all high frequencies up to a cutoff frequency \(f_c\), without affecting the low frequencies \((f \leq f_c)\), our ideal brick wall filter would exhibit an amplitude (frequency) response resembling the plot shown below.

Such ideal filter is the simplest theoretical lowpass filter. The gain is 1 in the passband, which pans frequencies from 0 Hz to the cutoff frequency \(f_c\) Hz, and its gain is 0 in the stopband (all frequencies above \(f_c\)). Such a perfect lowpass filter has magnitude responses

such that it passes all frequencies below cutoff \(\omega_c\) abd completely blocks all frequencies above the cutoff. The transition is infinitely sharp! In practice this is impossible because we would need an infinite-length impulse responses and negative-time samples (but we cannot look into the future).

A Very Simple Filter#

Another simple (and by no mean ideal) lowpass filter that we can define by a simple formula is give by the differential equation:

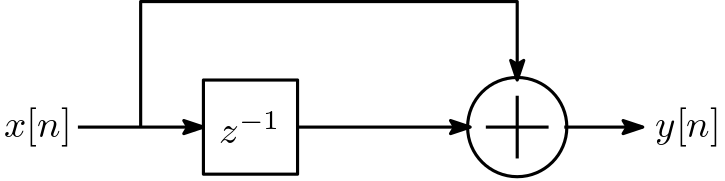

where \(x[n]\) is the filter input amplitude at time (or sample) \(n\), and \(y[n]\) is the output amplitude at time \(n\). We can also draw a signal flow graph for this little filter:

Fig. 30 Signal flow graph of the diffential equation filter.#

The \(z^{-1}\) symbol means a delay of one sample, i.e., \(z^{-1} x[n] = x[n-1]\).

It is important when working with spectra to be able to convert time from sample-numbers to seconds. Thus, a more physical way of writing equation Eq. (45) is given by

where \(T\) is the sampling interval in seconds. It is convinient in digital signal processing to omit \(T\), i.e. set \(T = 1\), but anytime you see \(n\) you can translate to seconds by thinking \(nT\).

We can easily define such a filter in sclang:

(

var simpleFilter = { |in, xm1=0|

var out = Array.newClear(x.size);

out[0] = in[0] + xm1;

for(1, in.size-1, { |n|

out[n] = in[n] + in[n-1];

});

out

};

x = [1,2,3,4,5,6];

// [ 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 ]

y = simpleFilter.(x);

)

The variable xm1 can be referred to as the filter’s state, representing the filter’s current memory at the time of invoking simplp.

This filter is characterized as a first-order filter due to it having a single sample of state.

It is essential to preserve the state of the filter after processing each segment of a signal.

Therefore, the state of the filter following the completion of block \(m\) becomes the initial state for processing the subsequent block \(m+1\).

You might suspect that since Eq. (45) is the simplest possible low-pass filter, it is also somehow the worst possible low-pass filter. How bad is it? In what sense is it bad? How do we even know it is a low-pass at all? The answers to these and related questions will become apparent when we find the frequency response of this filter.

In any case, we could use a input sinusoid and compute the resulting output signal. Let

If we apply Eq. (45), we get

Let us use \(A_1 = 1\) and \(f = f_s/4 = 1/(4T)\) and \(\phi_1 = 0\). Then the output sinusoid is given by

with \(A_2 \approx 1.414\), \(f = f_s / 4\), and phase \(\phi_2 = -\pi / 4\). This tells us how one specific frequency is influenced by the filter. The gain \(G(2 \pi f) = A_2 / A_1 = A_2 \approx 1.414\).

Gain of a Single Frequency of an LTI Filter

If the input to any LTI filter is a complex waveform \(A \cdot e^{i 2\pi f t}\), the output will be some constant times the input \(B \cdot e^{i 2 \pi f t}\) and the gain \(G(2 \pi f)\) is defined by

What we desire is a formula that gives us the amplitude response and the phase response for all frequencies, that is, the frequency response \(H(e^{i \omega T})\) of the filter. In the general case, this is a hard problem but for linear time-invarient filters we know how to compute it.

A Special Type of Filters#

Linear filters process time-varying input signals to produce output signals, subject to the constraint of linearity. In most cases these linear filters are also time invariant (or shift invariant) in which case they can be analyzed exactly using LTI (linear time-invariant) system theory.

Linear Time-invariant Filters (LTI)

Let \(x[n]\) be the input signal and \(y[n]\) be the output signal of a filter. Then a filter is linear time-invariant if the following two conditions hold:

Linearity: \(a \cdot x[n]\) translates to \(a \cdot y[n]\) and \(x_1[n] + x_2[n]\) translate to \(y_1[n] + y_2[n]\) (superposition principle).

Timeinvarianze: whether we apply an input to the filter now or some time later does not matter. The filters effect does not change over time.

For example, if we modulate the cutoff frequency of a filter, it is no longer time-invariant. To analyse the behaviour of a linear filter one looks at two different effects.

The frequency response \(H\) in the frequency domain (\(z\)-plane): how does the amplitude and phase of a frequency \(f\) changes.

The impulse response \(h\) in the time domain: how does the amplitude over time change.

From here onwards we define \(\omega := 2 \pi f\).

Frequency Response#

The frequency response of a filter tells us how it effects the amplitude and phase of a frequency of the input signal. For LTI filters it is defined as the spectrum of the output signal divided by the spectrum of the input signal, that is,

where \(X(z) = \mathcal{Z}\{x[n]\}\) and \(Y(z) = \mathcal{Z}\{y[n]\}\) are the \(z\)-transform of the input and output signals and \(H(z)\) is the filter transfer function. If we set \(z = e^{i \omega T}\) in the definition of the \(z\)-transform, we obtain

which may be recognized as the definition of the bilateral discrete time Fourier transform (DTFT) when \(T\) is normalized to 1. Applying this relation to \(Y(z) = H(z) X(z)\) gives

Therefore, the spectrum of the filter output is just the input spectrum times the spectrum of the impulse response.

Frequency Response of an LTI Filter

The frequency response of a linear time-invariant filter equals the transfer function \(H(z)\) evaluated on the unit circle in the \(z\)-plane, i.e., \(H(e^{i \omega T})\). This implies that the frequency response of an LTI filter equals the discrete-time Fourier transform of the impulse response.

Since \(e\), \(i\), and \(T\) are constants, the frequency response \(H(e^{i \omega T})\) is only a function of radian frequency \(\omega\). Since \(\omega\) is real, the frequency response may be considered a complex-valued function of a real variable. The response at frequency \(f\) Hz, for example, is \(H(e^{i 2 \pi f T})\), where \(T\) is the sampling period in seconds.

It is convinient to define a new function such as

and write \(Y'(\omega) = H'(\omega) X'(\omega)\) instead of having to write \(e^{i \omega T}\) all the time. However, doing so would add a lot of new functions to an already notation-rich scenario. Furthermore, writing \(H(e^{i \omega T})\) makes the connection between the transfer function and the frequency response explicit. We have to keep in mind that by defining the frequency response as a function of \(e^{i \omega T}\), we place the frequency ‘axis’ on the unit circle in the complex \(z\)-plane, since \(|e^{i \omega T}| = 1\).

As a result, adding multiples of the sampling frequency to \(\omega\) corresponds to traversing the whole cycles around the unit circle, since

whenever \(k\) is an integer. Since every discrete-time spectrum repeats in frequency with a ‘period’ equal to the sampling rate, we may restrict \(\omega T\) to one traversal of the unit circle. A typical choice is

For convenience, \(\omega T \in [-\pi, \pi]\) is often allowed.

Because every complex number \(z\) can be represented as a magnitude \(r = |z|\) and angle \(\theta = \angle z\), i.e., \(z = r \cdot e^{i \theta}\), the frequency response \(H(e^{i \omega T})\) may be decomposed into two real-valued functions, the amplitude response \(|H(e^{i \omega T})|\) and the phase response \(\angle H(e^{i \omega T})\).

Frequency, Amplitude, and Phase Response

The frequency response of a linear time-invariant filter can be represented in one formula:

where \(G(\omega T) := |H(e^{i \omega T})|\) is the amplitude (frequency) response and \(\mathcal{\Theta}(\omega T) := \angle H(e^{i \omega T})\) the phase response of the filter.

Analysis of a Simple Filter#

Let \(x[n]\) be an input signal, \(y[n]\) the output signal of the filter and \(f_s = \frac{1}{T}\) the sample rate. Let us start with a very simple filter:

Note that \(x[t]\) is defined for \(t = n T\) with \(n = 0, 1, 2, \ldots\) Our simple filter is a linear and time-invariant filter. The OneZero unit generator is a flexible version of this filter.

You might suspect that, since it is the simplest possible lowpass filter, it is also somehow the worst possible lowpass filter. How bad is it? In what sense is it bad? How do we even know it is a lowpass filter at all? The answers to these and related questions will become apparent when we find the frequency response of this filter.

Our goal is to use a test singal that consists of only one frequency and then reformulate \(y[n]\) such that we arrive at

where \(H(e^{i \omega T})\) has to be independent of \(n\).

We start by using test signals, i.e., we define \(x[n]\) to be a sinusoid containing one specific frequency \(f\). Therefore, we assume:

// here we test for f = f_s / 5

(

{

var sig = SinOsc.ar(s.sampleRate/5);

[sig, OneZero.ar(sig, coef: 0.5, mul: 2)]

}.plot(20/s.sampleRate)

)

Let us simplify by assuming \(A = 1\), \(\phi = 0\) and \(\omega = 2\pi f\) thus

Therefore, \(y[n]\) is defined by

We get the same solution as we got using the \(z\)-transform. The gain for this filter is

and the phase response is

We can further manipulate the formula for the gain by the following:

using

we get

Thus

Because of the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, we can assume that we only look at frequencies \(f\) such that \(-f_s/2 \leq f \leq +f_s / 2\) holds. Therefore, the equation simplifies to

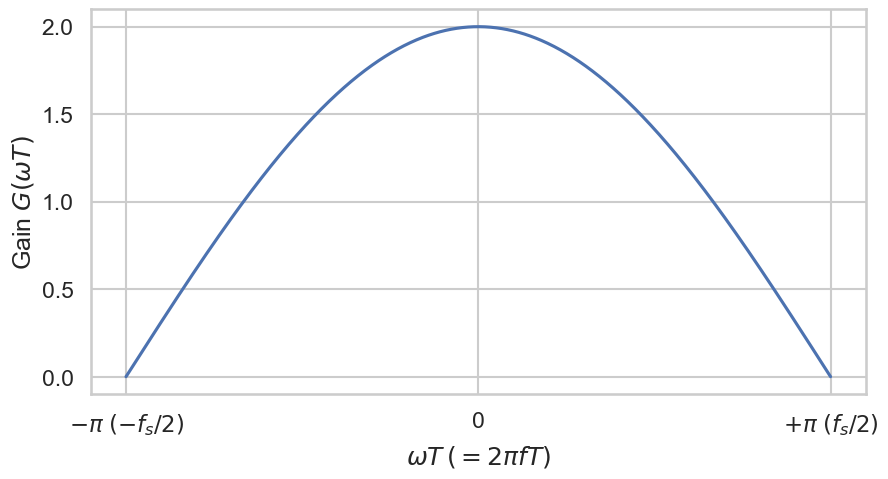

for \(-\pi \leq \omega T < \pi\). The following plot shows the amplitude frequency response in \(\omega\).

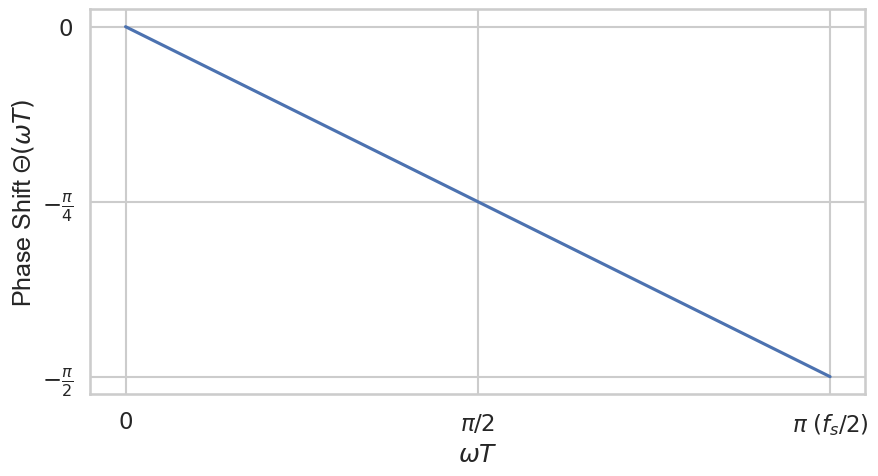

Secondly we look at the phase response

The plot looks like the following figure.

This lowpass filter has no phase delay at 0 Hz and a maximum delay of \(-(\pi/2)\) at the Nyquist frequency

Note that both responses rely on the sample period \(T = 1 / f_s\). If we increase the sample rate, the loss in power of high frequencies decreases! To achieve a similar result, we have to adapt the coefficients of the filter equation accordingly.

Low- and High-Level Filters

The frequency response of low-level SuperCollider filters, such as OneZero, OnePole, FOS, SOS rely on the sample rate \(f_s\). High-level filters such as LPF and HPF do not! Therefore, they are much easier to use.

Furthermore, the phase shift depends on \(\omega\). It looks like this might lead to a phase distortion, however, this frequency-dependent delay is counteracted because doubling the frequency of the input halves its period, balancing the growth in retardation introduced by the filter. This linear dependence is actually necessary.

Linear Phase Filters

If the phase response of the filter is a linear (straight-line) function of frequency (excluding phase wraps at \(\pm 180\) degree), the filter is said to be linear phase.

Filters that are not linear phase can introduce phase distortion.

General Form of a LTI Filter

An LTI filter may be expressed in general as follows:

Thus, a filter can be characterized as circular motion with radius \(G(\omega T) A\) and phase \(\Theta(\omega T)+\phi\). The particular kind of filter implemented depends only on the definition of \(G(\omega T)\) and \(\Theta(\omega T)\).

One Zero Filter#

In SuperCollider the one zero filter OneZero realizes the following formula:

we have \(N = 0\) and \(M = 1, a_0 = 1, b_0 = (1 - |\alpha|), b_1 = \alpha\). We can use the transfer function of LTI filters to analyse the effects of the filter. Using the Z-transform, we get

There is a pole at \(z = \infty\) and a zero at \(z = \frac{\alpha}{|\alpha|-1}\). Therefore,

If we evaluate the transfer function \(H(z)\) for \(\alpha = 0.5\) at the frequncies of interest we get the frequency response:

which is similar result we got in the last section!

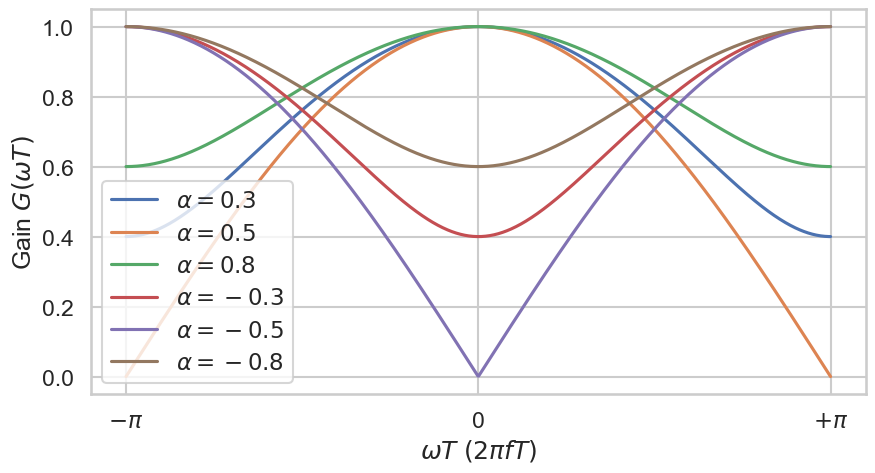

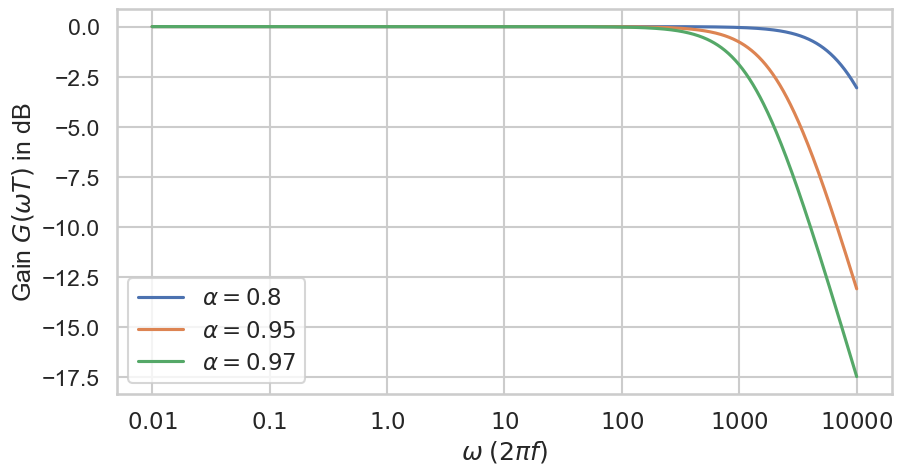

Let us plot the gain in frequency for \(T = 1\) and different \(\alpha\):

Fig. 31 Gain of zero one filters with respect to the parameter \(\alpha\). There is no parameter for the cutoff frequency.#

The unit generator OneZero got his name by the fact that it has one zero.

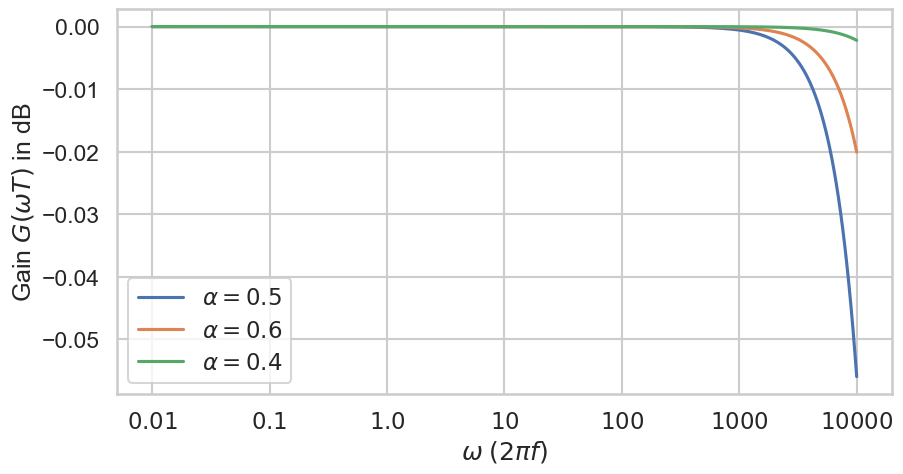

Remember that the filter completely filters \(f_s/2\). But since \(f_s = 44100\) the overall effect of the filter hardly audible. Without a pole the filtering effect is weak. This can be illustrated by using \(T = 1/f_s\) with \(f_s = 44 100\) for the plot combined with a log-scale:

Fig. 32 Gain of zero one (lowpass) filters in dB with respect to the parameter \(\alpha\) on a log-scale using \(T = 1 / 44100\). There is no parameter for the cutoff frequency.#

(

{ WhiteNoise.ar(0.3!2) }.play;

)

(

{

var alpha = 0.95;

OneZero.ar(WhiteNoise.ar(0.3!2), alpha);

}.play;

)

One Pole Filter#

In SuperCollider the one pole filter OnePole realizes the following formula:

we have \(N = 1\) and \(M = 0, a_0 = 1, a_1 = -\alpha, b_0 = (1 - |\alpha|)\) Therefore,

There is a pole at \(z = \alpha\) and a zero at \(z = \infty\). Therefore,

If we evaluate \(H(z)\) for \(\alpha = 0.5\) at the frequncies of interest we can see the frequency response:

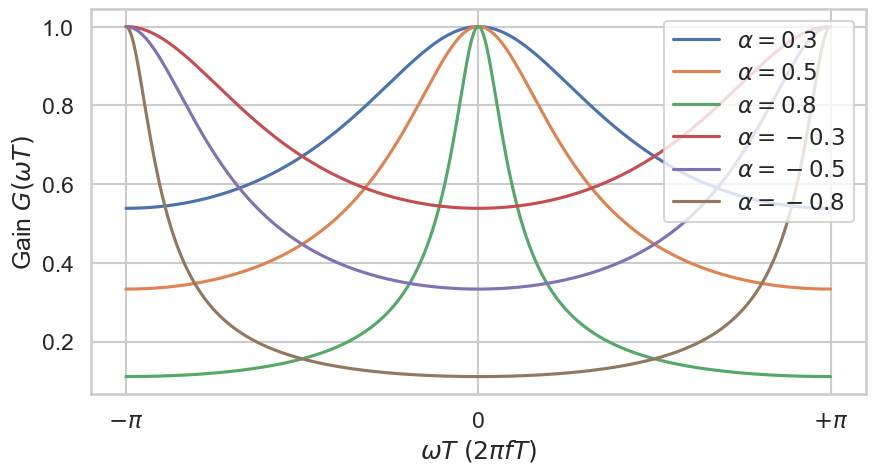

Let us plot the gain in frequency for \(T = 1\) and different \(\alpha\):

Fig. 33 Gain of one pole filters with respect to the parameter \(\alpha\). There is no parameter for the cutoff frequency.#

This explains the name of the unit generator OnePole. It got his name by the fact that it has one pole. Compared to the one zero filter it is able to have a much steeper drop / increase in gain. Similar to the one zero filter it is a low pass filter for positive \(\alpha\) and high pass filter for negative \(\alpha\). For both these filters, the cutoff frequency \(f_c\) is equal to 0 Hz, i.e., all frequencies are effected.

If we use a sample frequency \(f_s = 44 100\) Hz, then we get the following realistic result below. As you can see, we have to choose \(\alpha\) close to \(1.0\) to achieve a drop in gain across audible frequencies.

Fig. 34 Gain of one pole (lowpass) filters in dB with respect to the parameter \(\alpha\) on a log-scale using \(T = 1 / 44100\). There is no parameter for the cutoff frequency.#

(

{ WhiteNoise.ar(0.3!2) }.play;

)

(

{

var alpha = 0.95;

OnePole.ar(WhiteNoise.ar(0.3!2), alpha);

}.play;

)

Butterworth Filter#

The default low- and highpass filters unit generators (LPF and HPF respectively) of sclang, filter frequencies above or below some cutoff frequency.

They are 2nd order Butterworth low-/highpass filter.

Analog Butterworth Filter#

A Butterworth filter is defined in the analog domain (Laplace transform, \(H(s)\)), not natively in the \(z\)-domain. The gain \(G(\Omega)\) of the a \(n\)-order analog Butterworth low-/highpass filter is defined by:

where \(\Omega_c\) is the cutoff frequency (radian/seconds). Note that we are currently looking at an anlalog signal thus we do not use \(H(e^{i \omega T})\) but \(H(i \Omega)\).

The poles of \(H(s)\) are placed evenly on a semicircle in the left-half \(s\)-plane. So in the Laplace domain:

where \(s_k\) are the Butterworth poles.

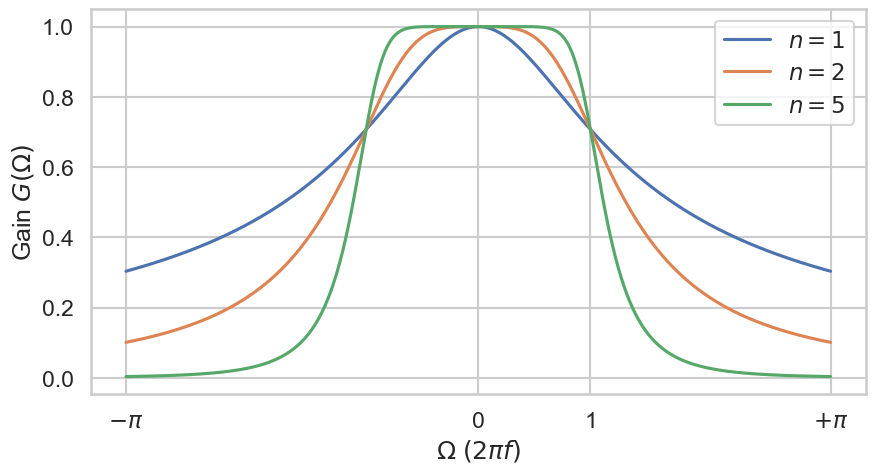

The frequency response of a 2nd order analog Butterworth lowpass filter is illustrated below. \(n\) is the order as well as the number of poles of the filter. The filter reduces the gain (amplitude) for frequencies above the cutoff frequency and shifts their phases. Well, that is not entirely true because the cutoff frequency is also reduced by 6 decibel (dB), so the reduction starts a little bit below the cutoff frequency. Reducing the loudness by 6 dB means that the perceived level is reduced by a factor of 4.

Fig. 35 Gain of the analog Butterworth filters of order \(n\) where the cutoff frequency is equal to 1.0.#

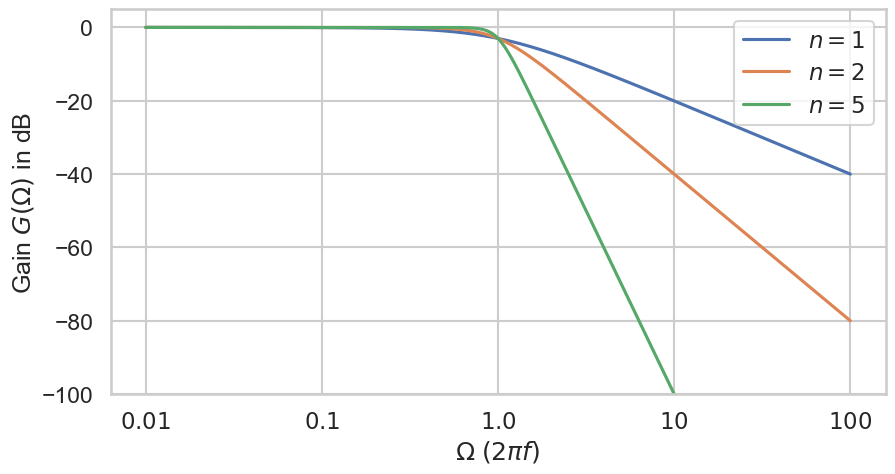

We can change the scaling of our axis to display gain in decible and to reflect the exponential character of frequencies.

Fig. 36 Gain in dB of the analog Butterworth lowpass filters of order \(n\) on a log-scale where the cutoff frequency is equal to 1.0.#

The second effect of the filter is a phase shift. This effect is crucial if we combine multiple filters because they interact! In other words: we can not just combine a high pass and lowpass filter to get the same result as a band pass filter!

Digital Butterworth Filter#

To convert the digitalize the analog filter we can apply the so called bilinear transform. It is a first order Padé approximant of the natural logarithm function that is an exact mapping of the \(z\)-plane to the \(s\)-plane, where \(s := i \omega\).

When the Laplace transform is performed on a discrete-time signal (with each element of the discrete-time sequence attached to a correspondingly delayed unit impulse), the result is precisely the \(z\)-transform of the discrete-time sequence with the substitution of

The inverse of this mapping (and its first-order bilinear appoximation) is

where \(T = 1/f_s\) is the sampling period. After substitution, the analog transfer function \(H(s)\) becaomes:

This gives you a rational function in \(z^{-1}\):

where \(B\) and \(A\) are polynomials determined by filter order and cutoff.

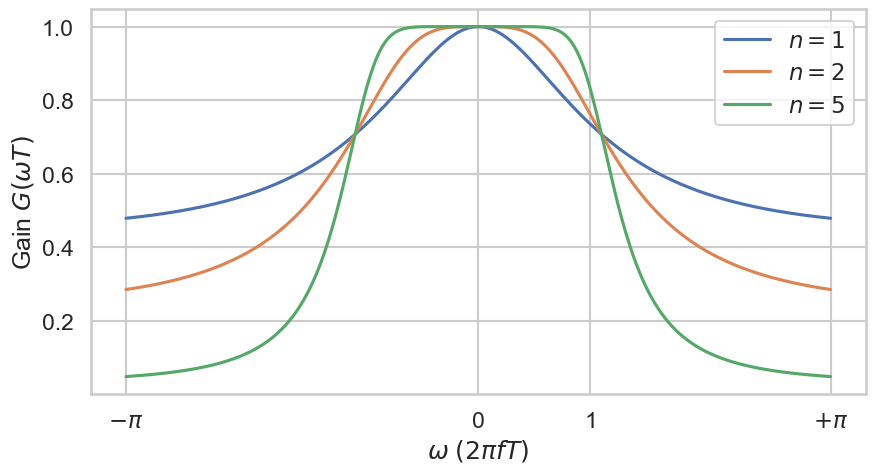

The approximated gain \(G(\omega T)\) of the a \(n\)-order digital Butterworth low-/highpass filter is defined by:

Plotting this function gives not the same result compared to the analog version. There is a clear difference.

Fig. 37 Gain of the approximation of the digital Butterworth filters of order \(n\) where the cutoff frequency is equal to 1.0.#

(

{ WhiteNoise.ar(0.3!2) }.play;

)

(

{

var cutoff = 600;

LPF.ar(in: WhiteNoise.ar(0.3!2), freq: cutoff);

}.play;

)

2nd Oder Butterworth Lowpass Filter#

Let us look at the formulas for an analog second-order Butterworth filter. We have

The poles lie on a semicircle of radius \(\Omega_c\) in the left half \(s\)-plane, at angles

For \(n=2\), the poles are at 135 and 225 degrees:

The denominator polynomial (monic) formed from these poles is

Choosing the DC gain to be 1 gives the analog transfer:

To implement digitally, map \(s\) to \(z\) with the bilinear transform:

Because the bilinear transform warps frequency, prewarp the desired digital cutoff \(\omega_c\) (radian/sample) to the analog cutoff:

It’s convenient to set

Now we substitute \(s = \frac{2}{T}\frac{1-z^{-1}}{1+z^{-1}}\) and \(\Omega_c = \frac{2}{T} K\) into (49), clear the \((1+z^{-1})\) factors, and collect powers of \(z^{-1}\). After simplifying and normalizing so that \(a_0 = 1\), you get biquad:

with the Butterworth lowpass coefficients (unity DC gain):

That’s the standard 2nd-order digital Butterworth low-pass centered at cutoff \(f_c\) (or \(\omega_c\)) with sampling rate \(f_s\).

Impulse Response#

Another fundamental result in LTI system theory is that any LTI system can be characterized entirely by a single function called the system’s impulse response (in the time domain). The output of the filter \(y[n]\) is given by the convolution of the input of the filter \(x[n]\) with the system’s impulse response \(h[n]\), that is,

Impulse Response

The impulse response, or impulse response function (IRF), of a filter is its output when presented with a brief input signal, called an impulse \(\delta(t)\). In the discrete case this the impulse is defined by the Kronecker \(\delta\)-function \(\delta[n]\).

The Dirac delta distribution (\(\delta\) distribution), also known as unit impulse, is a generalized function or distribution over the real numbers, whose value is zero everywhere expect at zero, and whose integral over the entire real line is equal to one:

Strictly speaking \(\delta(t)\) not a function because it is not defined for \(\delta(0)\). One can define

Interestingly, the Dirac delta function is the neutral element of the convolution, that is,

In the discrete case, things are more intuitive via the Kronecker delta function \(\delta[n]\).

Kronecker \(\delta\)-Function

The Kronecker delta function \(\delta : \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \{0, 1\}\) is defined by

It is the discrete analog of the Dirac delta function. For example, the filter response of our simple filter is

which gives us \(h[0] = h[1] = 1\) and \(h[n] = 0\) for all \(n \geq 2\). Note that any signal \(x[\cdot]\) can be expressed as a combination of weighted delta functions, i.e.,

FIR Filter

A filter with a finite impulse response, e.g. echos, is called final impulse response (FIR) filter. All filters of the form

are FIR filters.

A one zero filter is a FIR filter. A one pole filter is a infinite impulse response (IIR) filter since the feedback process will create an endless number of decaying impulses.

IIR Filter

A filter with a infinite impulse response, e.g. echo with feedback, is called infinite impulse response (IIR) filter.

Let’s look at the one pole filter with \(\alpha = 0.5\) for simplification. We get

whith \(h[0] = \delta[0] = 0.5\). It follows that \(h[1] = 0.25\), \(h[2] = 0.125\) and in general

In other words the impulse response \(h\) converges to zero \(\lim_{n \leftarrow \infty} h[n] = 0\) but never reaches it. If we compute the discrete-time Fourier transform of \(h[\cdot]\) we should get the frequency resonse \(H(e^{i \omega T})\):

Note that the last step is non-trivial!