Reverberation#

Reverberation, often shortened to reverb, is a phenomenon where sound waves reflect off surfaces, resulting in a large number of echoes that gradually fade or “decay”. It gives us a sense of the size and type of space we’re in, whether it’s a small bathroom or a large cathedral.

Reverberation depends on our capability to recognize events in time. As we know, our conscious is blind for very slow and vey fast processes with repect to time. We can think about and measure day and night, month, year and the air pressure change of the weather but we can not perceive them immediately. Furthermore, if pulses arrive in a distance smaller than 60 milliseconds, we can hear a sound but we can nor perceive the dynamic—the underlying movement in time. Our sense of time relates to the rhythms of the body, e.g., our heart beating, our breathing and walking speed (which decreases with age).

There are different time constants known from perceptual psychology which determine the perception of the human hearing:

Two arbitrary acoustic signals within 2 ms or less are perceived as simultaneous.

Multiple similar acoustic signals within about 40 ms can blend to one perception. If the signals are different a occultation might occur.

Two similar acoustic signals within about 100 ms or more are preceived as an echo.

The integration time of our hearing, that is, the time interval over that we sum up acoustic signals to control the sensation of loudness, amounts to about 300 ms.

Let test this. Firt we introduce a synth that is just simple decaying impulse.

(

SynthDef(\imp, {

var sig = Decay.ar(Impulse.ar(0), 0.2) * PinkNoise.ar;

DetectSilence.ar(sig, doneAction: Done.freeSelf);

Out.ar(0, sig!2);

}).add;

)

Let’s play the synth two times with a delay of 2 ms. I at least can not hear the second impulse.

(

fork {

Synth(\imp);

(2.0 / 1000.0).wait;

Synth(\imp);

}

)

Let us play it within 40 ms. I can hear two impulses. However, they are however blended together.

(

fork {

Synth(\imp);

(40.0 / 1000.0).wait;

Synth(\imp);

}

)

Using an interval of 100 ms creates an echo effect.

(

fork {

Synth(\imp);

(100.0 / 1000.0).wait;

Synth(\imp);

}

)

And, to be consistent, let’s listen into the effect of an interval of 300 ms.

(

fork {

Synth(\imp);

(300.0 / 1000.0).wait;

Synth(\imp);

}

)

The effect of perceiving a single auditory event if a sound is followed by another sound separated by a sufficiently short delay smaller than 40 ms is also called the Haas effect. The lagging sound also affects the perceived location but its effect is suppressed by the first-arriving sound, i.e., the first wave front.

If we start shouting in a big concert hall, we will receive an echo. If the time between the initial shouting and the echo is short enough, we perceive reverberation. The sound wave gets reflected to us, and the reflected wave might get reflected again and again. Architects have these reflections in mind when they build a concert hall. Moreover, an instrument’s timbre is determined by the instrument and how it is played, and in what environment it is played.

Humans are capable of separating sound sources from each other – even in the absence of localization cues. For example, we can usually easily separate an oboe from a flute, and a flute from a violin, even though they play in the same register. The melody from the oboe will be heard separately from the melody of the flute. Both instrumental lines from a sound stream – just like the words of a particular person in a party from a stream. These streams are examples of foreground streams. They carry specific and often different content and meaning, and we can choose to listen to one while excluding the other.

As long as a person is talking, the reverberation sounds continuous and has a constant level. At that point, it is a background stream. However, if we look at the sound signal on an oscilloscope, it is clear that the reverberation is decaying rapidly between syllables. When the speaking person stops, the reverberation becomes a foreground stream and is audible as a distinct sound event. Under these conditions, it is easy to hear that it is decaying.

The human hearing generally waits about 40 milliseconds after a sound event’s apparent end, before deciding it is over. Therefore, we perceive multiple sound cues within a period smaller than 40 ms as one continuous stream. Early reflections can be used to alter the timbre of a sound; to make it louder, heavier, spacially more interesting.

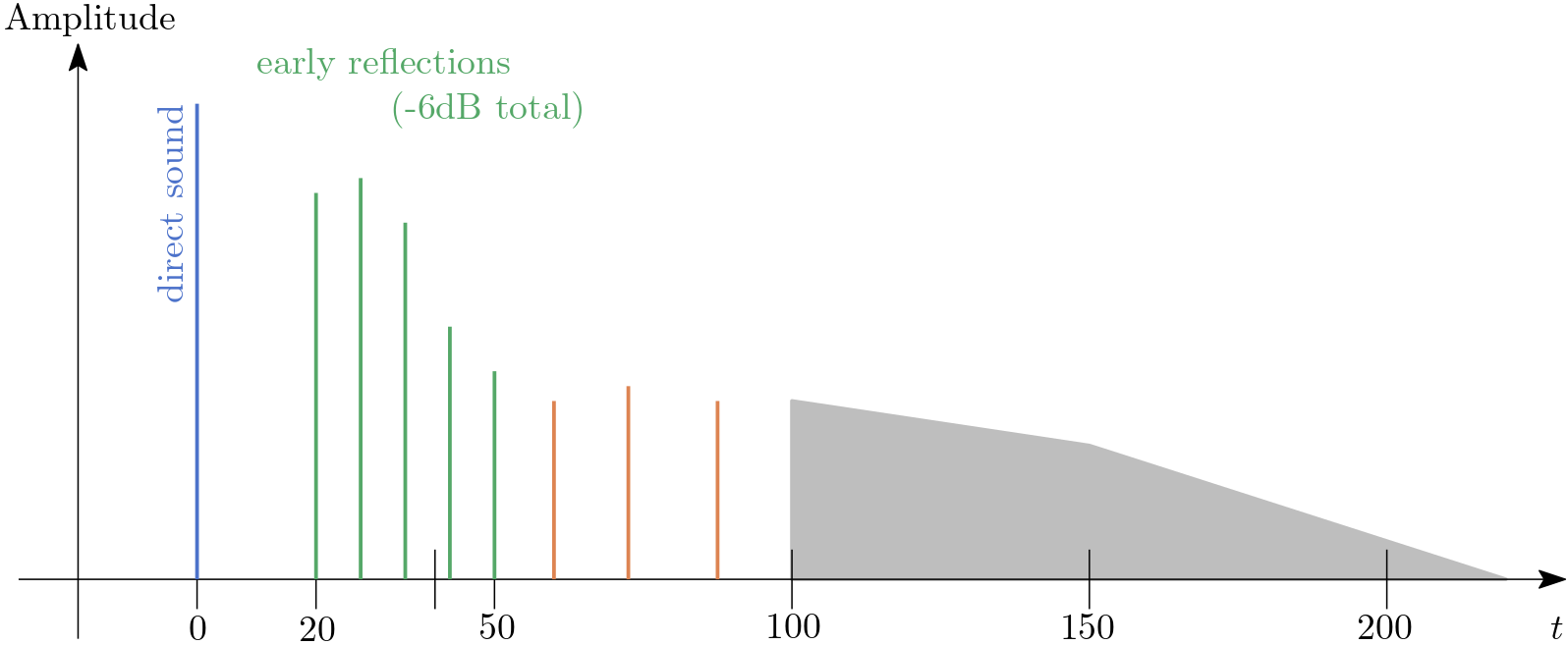

Fig. 60 Ideal reverberation profile (according to D. Griesinger). Time \(t\) is measured in milliseconds.#

In The Theory and Practice of Perceptual Modeling – How to use Electronic Reverberation to Add Depth and Envelopment Without Reducing Clarity (pdf) presented at the Tonmeister conference (2000) in Hannover, David Griesinger gives an excellent description of an ideal reverberation profile for recording. We need a strong early lateral field for producing a sense of distance, a mimimum of energy in the \(50-150\,\text{ms}\) region, and adequate reverberant energy after \(150\,\text{ms}\). Recordings with too much energy in the \(50\) to \(150,\text{ms}\) region sound muddy. This time range must be carefully minimized.

Reverberation can be simulated/approximated by adding delayed signals that decay over a certain amount of time to the overall output.

Single Reflection#

DelayN takes an input signal, delays it for delayTime (in seconds) and outputs the a delayed copy (without the original).

Therefore, it can be useful to introduce a reverb effect.

In the following example we use a decaying impulse to generate a repeating exponential envelope.

The Impulse decays over a period of 0.2 seconds.

Decay works similar to Integrator which basically integrate an incoming signal, which is another way of saying that it sums up all past values of the signal.

It realizes the following formular:

which is realized inductively by

Decay operates on the basis of more meaningful parameters which are independent from the sample rate. We multiply this repeating envelope with a PinkNoise to get a simple beat. The decaying impulse is just a line going to zero.

{Decay.ar(Impulse.ar(1.0), 0.2) * PinkNoise.ar}.play

Let’s add a delayed copy:

({

var sig = Decay.ar(Impulse.ar(1.0), 0.2) * PinkNoise.ar;

sig + DelayN.ar(sig, 0.5, delaytime: 0.15);

}.play;

)

If you want to modulate the delay time you should consider the interpolated versions, i.e., DelayL or DelayC.

Decaying Reflections#

A CombN delay line with no interpolation is a delay with feedback, i.e., the signal is fed back into the delay. The signal’s power is reduced each time it is fed into the delay. The decay time is the period (in seconds) for which the signal decays by 60 decibels. Let’s have a listen:

({

var decaytime = 2.0;

var sig = Decay.ar(Impulse.ar(1.0), 0.5) * PinkNoise.ar;

sig + CombN.ar(sig, 0.5, delaytime: 0.15, decaytime: decaytime);

}.play;

)

We can generate some exciting grain sounds by combining modulated resonance with a comb delay line:

({

var centerFreq = LFNoise0.kr(40/3).exprange(20, 1800);

var sig = Saw.ar([32,33]) * 0.2;

sig = BPF.ar(sig, freq: centerFreq, rq: 0.1).distort;

sig = CombN.ar(sig, 2, delaytime: 2, decaytime: 40);

sig;

}.play;

)

The AllpassN unit generator implements a Schroeder allpass filter. It works and sounds very similar to the comb delay line but allpass filters change the phase of signals passed through them. For this reason, they are useful even though do not seem to differ much from comb filters.

({

var decaytime = 2.0;

var sig = Decay.ar(Impulse.ar(1.0), 0.5) * PinkNoise.ar;

sig + AllpassN.ar(sig, 0.5, delaytime: 0.15, decaytime: decaytime);

}.play;

)

Plucking#

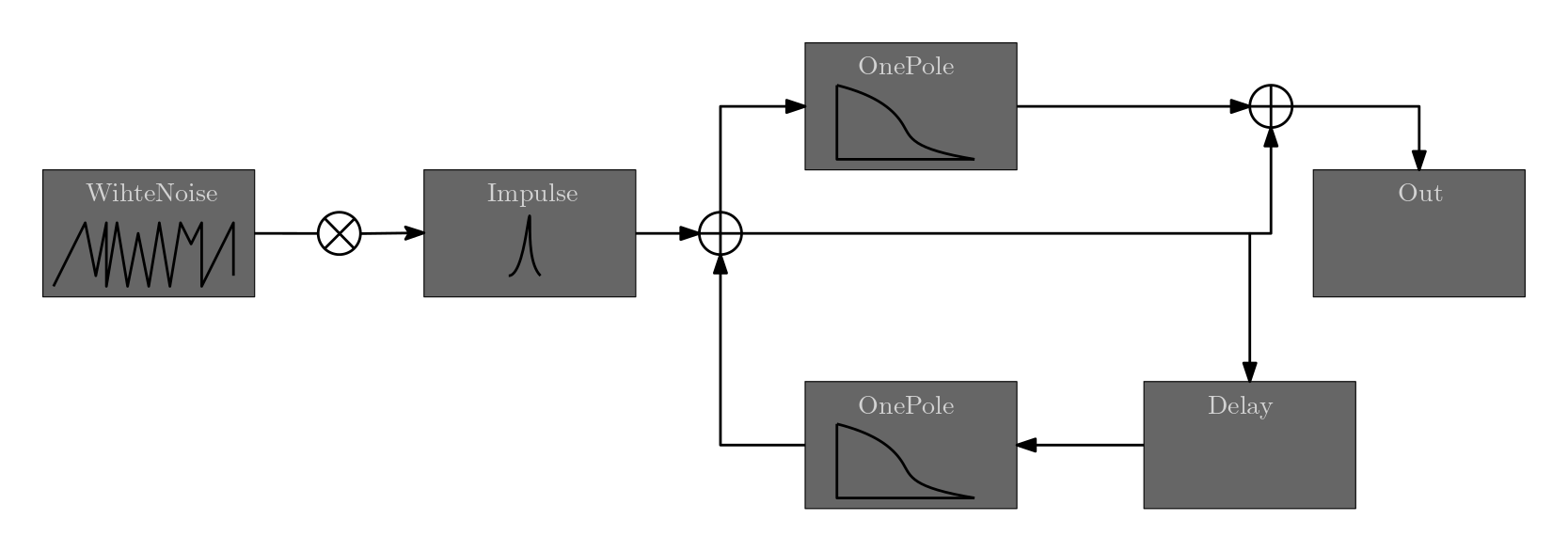

The Pluck unit generator realizes a Karplus-Strong string synthesis which is a method of physical modeling that loops a short waveform through a filtered delay line to simulate the sound of a hammered or plucked string or some types of percussion. The generator consists of a OnePole lowpass filter and a delay line.

In the following, I tried to recreate the pluck using basic unit generators. I use two synth definitions, one for the pluck and the other for the impulse generation. The impulse signal is fed into the pluck by using SuperCollider’s bus system. Evaluate each block one at a time from top to bottom.

// reconstrucktion of Pluck

(

SynthDef(\pluck,{

arg in, out;

var sig, dsig, local;

local = LocalIn.ar(2);

sig = In.ar(in, 2);

sig = sig + local;

local = OnePole.ar(DelayN.ar(sig, 0.01, 0.002), 0.3);

sig = OnePole.ar(sig, 0.3);

LocalOut.ar(local);

Out.ar(out, local + sig);

}).add;

)

// Impulses

(

SynthDef(\impulse, {

arg out;

var sig = WhiteNoise.ar(0.6) * Impulse.ar(2!2);

Out.ar(out, sig);

}).add;

)

(

~impulses = Group(s, \addToHead);

~synths = Group(s, \addToTail);

)

(

~impulse = Synth(\impulse, [\out, 4], ~impulses);

~pluck = Synth(\pluck, [\in, 4, \out, 0], ~synths);

)

I also make use of Groups, a concept I did not cover yet.

Groups help me to bring the synths in the right order on the audio server.

\impulse is a synth that outputs impulses of white noise.

This impulse is read by \pluck, therefore, \pluck has to operate after \impulse.

Since I add the ~impulse group to the head and the ~synths group to the tail, all synth in the ~impulse group operate before synths in the ~synths group.

The following signal flow graph shows how the output is computed.

Fig. 61 Signal-flow graph of the construction above.#

Using Pluck instread, generates a slightly different sound:

({

Pluck.ar(

in: WhiteNoise.ar(0.1!2),

trig: Impulse.kr(2),

maxdelaytime: 0.002,

delaytime: 0.002,

decaytime: 10,

coef: 0.3)

}.play;

)

Reverberation#

SuperCollider offers out of the box reverberation unit generators: FreeVerb, FreeVerb2, and GVerb.

In this example, I use grains sampled from a single sine wave that changes its frequency whenever the envelope is triggered.

\gverb applies reverb to the grain.

This time I do not make use of Groups, therefore, I have to be careful of the oder in which I add synth to the audio server.

(

SynthDef(\sin_grain, {

arg out = 0;

var n = 10, sig, env, trigger, freqs;

trigger = Dust.kr(5);

env = EnvGen.ar(Env.sine(0.02), trigger);

freqs = Dseq(Array.exprand(n, 100, 5000), inf);

sig = SinOsc.ar(Demand.kr(trigger, 0 ,freqs)) * env * \amp.kr(0.2);

sig = Splay.ar(sig);

Out.ar(out, sig);

}).add;

)

(

SynthDef(\gverb, {

arg in, out=0;

var sig = GVerb.ar(

in: In.ar(in, 1), // mono input

roomsize: 15, // in square meters

revtime: 3, // in seconds

damping: 0.13, // 0 => complete damping, 1 no damping

inputbw: 0.13, // damping control but on the input

spread: 15,

drylevel: 1,

earlyreflevel: 0.3,

taillevel: 0.1,

maxroomsize: 300);

Out.ar(out, sig!2);

}).add;

)

(

~gverb = Synth(\gverb, [\in, 4, \out, 0]);

~grains = Synth(\sin_grain, [\out, 4]);

)