Glossary#

Learning something now almost always includes learning a new language. In this reference section, I explain common terms.

Physics#

Sound Waves#

In nature, sound is produced by a vibrating object. These vibrations cause air molecules to oscillate. They bump into each other at some areas (compression) and tend to leave other areas (rarefaction). A pattern of lower and higher molecule density emerges.

Fig. 80 A pattern of lower and higher molecule density.#

On a larger scale, this change in air pressure is a mechanical wave that travels from the oscillating object, called oscillator, to other objects. Overall, we can think of sound as a mechanical wave that propagates from one place through the medium of transportation. The wave is energy that deforms the medium, i.e., it transfers energy from one place to the other.

Hearing Range#

The hearing range is the range of frequency that a being can perceive. The hearing range of humans is 20 Hz to 20kHz where cats go up to 75kHz and bats up to 200kHz. This does not mean that we can not perceive sound below 20 Hz but at this point it perceived as discrete clicks instead of a continues tone. Furthermore, we can hear minimal relative frequency differences very intensively. Experimenting with low frequencies can be very fun!

// triangle waveform below the human hearing range

({ LFTri.ar(10!2) * 0.25; }.play;)

Sound Power#

The sound power is a physical measure. It is the energy per unit of time emitted by a sound source in all directions. The sound power is measured in watt (W) and it is surprisingly small. For example, a complete concert orchestra and a thunder have roughly the power of only 1 watt.

Sound Intensity#

Sound intensity is sound power per unit area, i.e. watt per square meter. The sound we can perceive can have a surprisingly small intensity. The threshold of hearing \(TOH\) is

On other end, the threshold of pain \(TOP\) is

At that intensity we start suffering.

The sound intensity is measured in decibels (dB) which is a relative unit of measurement. A decibel is one-tenth of a bel: 1 dB equals 0.1 B. It expresses the ratio of two values of a power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale using 10 as the base.

Since the measure is relative, if we want to use a decibel scale, we have to fix it to a reference. It is convenient to start with

0 dB as the sound intensity of the threshold of hearing \(THO\)

whispering is about 15 dB

a library 45 dB

a normal conversation 60 dB

a toilet flushing 75-85 dB

a noisy restaurant 90 dB

a baby crying 110 dB

a jet engine 120 dB

a ballon popping 157 dB

If we follow that convention, we can compute the decibels of a sound intensity \(I\) by

where \(I_{TOH}\) is the sound intensity of the threshold of hearing.

The measurement is motivated by the perception of loudness of the human ear. Increasing the perceived loudness by a factor of 2 equates to rise of +3 dB. In other words: every increase of 3 dB represents a doubling of sound intensity or acoustic power.

We can use db instead of amplitude (amp) to control the loudness in sclang.

To convert db to amp use dbamp and ampdb to do the reverse operation.

0.dbamp; // equals 1 amp

1.dbamp; // 1.122018454302

(-3).dbamp; // 0.70794578438414

3.dbamp; // 1.4125375446228

For example, the sound generated by

{SinOsc.ar(400!2) * (-3).dbamp;}.play

should be perceived as approximately half the level of

{SinOsc.ar(400!2)}.play

Loudness#

Loudness is a subjective perception of sound intensity. It depends on the duration and frequency of a sound, and the age and other subjective properties of the listener. We perceive short-lasting sounds and sounds with a low frequency less loud than long-lasting high frequency sounds. Therefore, the sound intensity can be the same but the loudness can be very different. It is measured in phons.

Sound Design#

Signal#

A signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon.

Waveform#

The waveform of a signal is the shape of its graph as a function of time, independent of its time and magnitude scales and of any displacement in time. Waveforms can be periodic or aperiodic. A periodic waveform can be simple (e.g. a single sine wave) or complex and an aperiodic waveform can be continuous (e.g. noise) or transient (e.g. impulse).

The simplest and most fundamental waveform is a sinusoid

where the frequency \(f\) is the inverse of the period \(T\). The period \(T\) is the time at which the waveform repeats itself and the frequency \(f = 1/T\) is measured in hertz (Hz = cycles per second). \(A\) is the amplitude and \(\phi\) the phase of the waveform.

The frequency of a waveform determines the perceived pitch of the sound it produces. The higher the frequency the higher the pitch. Pitch is perceived on a logarithmic scale, that is, two frequencies are perceived similarly if they differ by a power of 2. 440 Hz is one octave above 220 Hz but we perceive it as the same tone. To increase the pitch by \(n\) octaves, we have to multiply the frequency by \(2^n\).

The amplitude of a waveform determines the perceived loudness of the sound. The higher the amplitude the louder the sound.

Timbre#

There is no measure of timbre. It is generally very hard to define it formally. It is often referred to as the color of a sound which does not explain anything but gives us an intuition.

Two different instruments can play the same note but we still can easily recognize the difference in the sound they generate. We may say an instrument sounds harsh, soft, dull and so on. Why is that? Well, because they have a unique timbre. This is even true for instruments of the same type, such as two violins.

If we define timbre as a relative subjective measure it is basically the difference in the harmonic (or inharmonic) spectrum over time. Let us imagine that a signal is the composition of the fundamental and infinitely many harmonics (and inharmonics). Each (in)harmonic \(h_i(t)\) is a sine wave with an amplitude \(A_i(t)\), that is, a function over time. The signal can be seen as a superposition of all (in)harmonic \(h_i(t)\) for \(i = 0, 1, \ldots,\). There are infinitely many different \(h_i\) thus infinitely many different sounds which represent the same note.

For example, both of the following synths generate the same note but have very different timbres:

({

var sig;

sig = SinOsc.ar(220)!2 * 0.5;

sig * EnvGen.ar(Env.perc(0.1));

}.play(fadeTime:0);)

({

var sig;

sig = LFSaw.ar(220)!2;

sig * EnvGen.ar(Env.perc(0.1)) * 0.5;

}.play(fadeTime:0);)

If we synthesize sound, we can achieve different timbres through:

the number and kind of harmonics or inharmonics of the signal,

resonance

However, this captures only the perspective of additive synthesis. Manipulating a very rich signal already composed of many harmonics is another way to achieve different timbres. This is called subtractive synthesis and makes use of filters.

Envelopes#

Envelopes partly form the timbre of an instrument. They control the amplitude of a waveform over time thus describe how a sound changes over time. In SuperCollider we create envelopes by combining envelope generators EnvGen and envelopes Env.

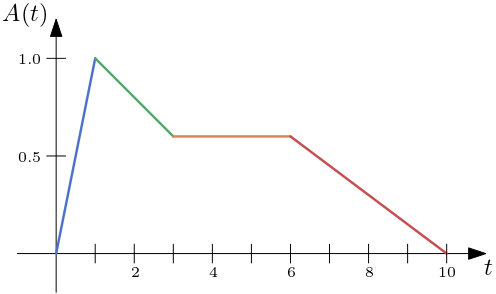

One of the most common kinds of envelope has four stages:

Attack is the time taken for the initial run-up of level from nil to peak. On a piano this is the beginning when the key is pressed.

Decay is the time taken for the subsequent run down from the attack level to the designated sustain level.

Sustain is the level during the main sequence of the sound’s duration. On a piano this is the level until the key is released.

Release is the time taken for the level to decay from the sustain level to zero after the key is released.

Fig. 81 ADSR envelope with an attack of 1 second, decay of 2 seconds, a sustain (level) of 0.6 and a release of 4 seconds.#

Another simpler envelope is the percussive envelope (for modelling percussive instruments) which has only two stages: a very short attack, and medium decay.

Of course each UGen can have its dedicated envelope.

If there is only one envelope that controls the amplitude of every involved partial, I call it the global envelope.

The envelope greatly influences the resulting sound. If we want to recreate the sound of a real instrument we have to match at least its global envelope. A piano has a very short attack (like a sixth of a second), a short decay followed by a varying sustain (depending on the pianist) and a rather short release.

The following code models the sound of a piano combining a sawtooth wave, a low pass filter to eliminate the harshness and an envelope with three stages (attack, decay, release). There is no sustain because we assume the pianist does not use the sustain pedal after hitting midi note 69.

(({

var sig, atk, dec, rel;

atk = 0.01;

dec = 0.07;

rel = 0.3;

sig = LPF.ar(LFSaw.ar(69.midicps), 2*69.midicps)!2;

sig * EnvGen.kr(Env(levels: [0, 1, 0.5, 0], times: [atk, dec, rel])) * 0.5;

}.play(fadeTime:0);)

In SuperCollider we can plot an envelope by sending the plot message to it.

Env(levels: [0, 1, 0.5, 0], times: [0.01, 0.07, 0.3]).plot

Compared to that, a violin has a long attack – the sound ramps up if the violinist accelerates the motion of his or her arm.

Legato#

With respect to the piano, legato means that a series of notes are played without a gap of silence. Before the pianist hits the next combination of keys when he or she sustains the previous keys. This concept is extended to wind and string instruments.

In SuperCollider the term is also used for its time conversion.

In this case it is a fraction, specifically a number greater than zero.

Playing a synth can be seen as a discrete event simulation.

Playing a note via a synth is an event in time.

The event has a delta \delta (basically the duration of the event) and a sustain (time) \sustain.

After the sustain (time), the decay starts.

And after the delta the next event starts.

Instead of specifying \sustain we can specify \legato that is translated to \sustain = \delta * \legato.

Therefore, legato in this context is a fraction of an event’s duration for which a synth should sustain. If legato is large, events will overlap.

Synthesis#

Low Frequency Oscillator#

A low frequency oscillator (LFO) is, as its name suggests, an oscillator that oscillates with a low frequency, that is, a frequency that is below the audible frequency. LFO’s are often used to control some argument of another oscillator, for example, to control its amplitude.

Ring Modulation#

Ring modulation (RM) is often used as a synonym for amplitude modulation (AM). Sometimes the term RM is used when the modulator is bipolar (the amplitude becomes positive as well as negative) and AM refers to a unipolar amplitude modulation. However, I stick to the term amplitude modulation (AM) to refer to both.