Art as Communication#

There is neither a medium without form nor a form without medium. The difference of mutual dependency and independency is pivotal. – Niklas Luhmann [Luh86]

In my essay Enframing and Poetry , I explored Heidegger’s understanding of art through my own lens. There, we approached art as an ontological event in which Being reveals itself, and where understanding is not merely a method or technique—but a fundamental mode of being (Dasein).

(Anti-)Humanism#

With Heidegger—and in contrast to many he influenced, such as Hans-Georg Gadamer or Jean-Paul Sartre—we enter a form of anti-humanism. This does not mean hostility toward human beings (as in misanthropy), but a philosophical stance that critiques the centrality of the human subject in traditional Western thought. Where humanism holds that human beings are the locus of meaning, truth, and value—rational, autonomous, and self-knowing agents—anti-humanism challenges this assumption. It seeks to dethrone the human subject from its privileged position, arguing that what we call “the subject” is not sovereign, but is constructed by language, discourse, structures, or systems. Meaning and agency, anti-humanists argue, are decentralized, dispersed across larger, often impersonal processes. There is no essence of “Man” that stands outside history, culture, or power.

The idea that humans are in charge of everything and at the center of meaning is an illusion.

I confess an emotional resistance to this anti-humanist view. It surfaces especially when I ask myself: What is art, and what qualifies something as a work of art? Even without formal training in art history or aesthetics, I find this question deeply compelling.

From a humanist perspective, art communicates an ineffable truth about existence. It challenges and disrupts by offering a glimpse into the infinite—or perhaps, the illusory. In the presence of the truly transcendent, we stand in awe, experiencing both relief and a profound connection to the essence of being. This description may be vague, but that is precisely the point: for me, the essence of art lies beyond the confines of language. This is why I recognize myself as broadly humanistic in my orientation toward art. In this view, art is a form of human expression—of emotion, genius, spirit, and experience. The artist becomes a creative subject, often romanticized, and the artwork is valued because it expresses the human condition.

In contrast, the anti-humanist position asserts that art is not about personal expression but about systems, structures, and processes of meaning. The artist, in this view (especially in Luhmann’s theory), is not a genius but an operator within a system of distinctions. Following Foucault, the author is a function—not the origin of meaning but a construct used to structure discourse and regulate interpretation [Fou79]. Meaning arises within the system [Luh97], not from individual intention. As Derrida argues, there is no final meaning in art—only différance, an endless deferral of meaning; interpretation is always unstable, never a simple decoding of the artist’s intent [Der82]. Art reflects the discursive formations of its time, not the isolated brilliance of an individual mind.

How long, then, will Husserl and Habermas be able to maintain their old or modern idea of critical reasons without becoming conservatives who stick to a tradition that cannot maintain its identity but fades away? – Luhmann [Luh95]

Despite my aversion—rooted in a humanist upbringing—I find the anti-humanist position deeply compelling. It offers a framework for sense-making in a complex world, one that doesn’t rely on the myth of the sovereign self. Therefore, I now turn to another German anti-humanist thinker, that is Niklas Luhmann, because he is so distinct from Heidegger and rather influenced by Hegel, Husserl, Kant, Derrida, and Deleuze.

From Being to Communication#

Although not a professional philosopher, the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann engages deeply with philosophical texts. He often regards philosophy as too focused on the subject and too non-operational—that is, insufficiently pragmatic for analyzing the complexities of modern society. Luhmann can best be understood as a philosophical sociologist—or more precisely, a sociologist of second-order observation. He operates at the edges of philosophy: not within its traditional frameworks, but alongside it, critiquing, absorbing, and reframing its core concepts within a systems-theoretical model.

Where Heidegger conceives of Being as the meaning of beings, Luhmann rethinks meaning (Sinn) as the medium through which psychic and social systems reduce complexity and maintain coherence over time. He is explicitly anti-ontological: rather than grounding theory in metaphysical foundations, he relies on operational distinctions—those that function within systems to generate and stabilize meaning. Whereas Heidegger privileges poetic language and art as sites where Being discloses itself, Luhmann treats art as a functional communication system that operates through observation, distinction, and variation.

The artwork sets truth to work. – Heidegger

Artworks are communications that distinguish between art and non-art. – Luhmann

Yet these positions are not entirely opposed. Luhmann’s notion that art makes perception communicable can be read as a system-theoretical reformulation of Heidegger’s idea that art opens up a world. But where Heidegger sees art as a moment of ontological disclosure, Luhmann sees it as a process of coding perception into communication—not a revealing of Being, but as a systemic transformation of perceptual experience (aesthetic perception) into communicative form—a process in which what is felt, seen, heard, or sensed is rendered communicable within the logic of the art system.

Medium and Form#

Luhmann offers a powerful and abstract framework for analyzing art by deploying his central distinction between medium and form, a conceptual pair inspired by Fritz Heider. For Luhmann, a medium consists of a vast multiplicity of loosely coupled elements—so numerous that any operation upon them necessarily involves selection. In the temporal dimension, these elements are events. Crucially, these are not objective entities like particles or Platonic constants, but rather constructed units, distinguished by an observing system. They do not determine themselves; their significance arises only through systemic coupling—that is, how the system relates them to one another to produce form.

A form, then, emerges from the rigid coupling of elements within a medium. The form condenses relations between selected elements, creating a stable configuration that stands out against the fluidity of the medium. It is essential to Luhmann’s epistemology that we never perceive the medium directly—we only perceive forms that indicate a structured relation among otherwise unstructured possibilities.

In Luhmann’s constructivist framework, this distinction replaces ontological binaries such as inside/outside or subject/object. Medium and form are not entities or substances; they are operational distinctions within a system. Without a system to enact and observe the distinction, neither concept has meaning. Like information, they are internal to the system—constructs, not things.

Because of this, medium and form are mutually dependent: there is no medium without the possibility of forming it, and no form that does not draw upon a medium. A medium becomes recognizable only through the contingency of possible form—constructions (Formbildung) it affords. The loose coupling of the medium’s elements refers to the wide range of potential relations that remain compatible with the integrity of each element. For example, the number of intelligible sentences that can be formed using a given set of words illustrates how linguistic forms emerge from the medium of language.

Luhmann defines medium and form relationally and hierarchically. What is form on one level may serve as medium on another. A sentence is a form drawn from the medium of language, but can itself be the medium from which larger narrative structures emerge. In other words, forms can recursively serve as the media of higher-order forms.

This logic allows Luhmann to model perception and communication together. A painting is a form drawn from the medium of all possible color arrangements. A performance selects from the space of all possible sound events or bodily movements. Each played tone is a form constructed from the medium of air vibrations—but importantly, in Luhmann’s constructivist terms, sound exists only for a listener. Without a system to perceive it, there is no “sound” as such—only an undifferentiated physical disturbance. In this way, Luhmann aligns with radical constructivism: reality is not given, but observed. Here I have to point out that this does not mean that nothing exists or that the mind creates reality! Constructivism is neither opposed to nor incompatible with realism.

The key relation between medium and form is selection. A computer program is a form selected from a programming language; a sentence from the grammar of a language; a painting from the medium of colors and strokes. And crucially, what is not selected remains present as unmarked space—a silent background of possibilities, always implied but never actualized. This links Luhmann’s theory to information theory: every form represents a reduction of complexity—a narrowing of the possible into a specific configuration. This is not a literal application of Shannon’s entropy formula [Sha48], but rather a structural analogy: each stroke, tone, or movement limits what can come next; it shapes the horizon of expectation.

Thus, the artwork becomes a contingent realization of form from within a medium. It could have been otherwise. And the observer knows this. This knowledge generates the central aesthetic tension: Why this form? What does it mean? What could have been done differently? The artwork must make sense under the condition of contingency—its necessity must appear within its radical openness to alternatives. In this sense, the singularity of the artwork is always in question, and therefore under judgment—by critics, by audiences, and by the art system itself.

Here, Luhmann departs decisively from any ontological, historical, or expressive theory of art. He is not primarily concerned with stylistic genres or cultural horizons of meaning, nor with an artwork’s truth or its relation to Being. Instead, he poses a more abstract, second-order question:

What is art beyond certain culturalistic, stylistic dependencies and genres?

To answer this, Luhmann uses the full abstraction of his system theory. He writes:

Artworks are not just traces of human activity […]. Neither do they arise as simple relicts of purposeful behavior—like tools, houses, streets or radioactive radiation. They serve […] as transmission of sense. – Niklas Luhmann

Art, then, is not the result of utilitarian action, nor an expression of human genius. It is a mode of communication within the autopoietic social system of art. This system is:

Autopoietic: it reproduces its own elements (artworks, observations, critiques) through its operations;

Operationally closed: it does not absorb elements directly from outside systems (e.g., economics or politics), but observes them and re-forms them internally;

Structurally coupled: it remains responsive to other systems (e.g., the market, media, science) while maintaining functional autonomy.

And its function?

Making perception communicable.

Art provides a form in which subjective experience—perception, emotion, reflection—becomes available to communication. This means art does not transmit a pre-existing message from artist to viewer; rather, it creates a space in which observers can generate meaning through second-order observation: observing how others observe the work.

In this way, Luhmann offers a theory of art that does not depend on the subject, on essence, or on expressive intention. Instead, it locates art’s specificity in its ability to transform aesthetic perception into communicable form—a distinction that allows the art system to reproduce itself through time.

Beyond the Subject#

We must be cautious with terms like “subjective experience”, as Luhmann does not operate within the object–subject paradigm. As noted earlier, he seeks to replace that distinction entirely, grounding his theory not in conscious intention or perception, but in communication. In his view, meaning does not reside in the subject, nor is it fixed or directly expressible. Instead, meaning emerges within the art system itself—through its historically accumulated forms, media, and communicative operations. A work of art does not “speak for itself”; it requires interpretive frameworks—exhibitions, criticism, academic discourse—to stabilize its meaning. Thus, art is neither reducible to psychology (e.g., artist intention) nor to sociology (e.g., audience behavior). It is its own autonomous subsystem of society, operating via its own code: art / non-art.

A medium cannot generate any form whatsoever; it can only yield those forms that are composable from its own elements. Medium and form share the same building blocks—the difference lies in how the elements are coupled: loosely in the medium, rigidly in the form. The medium thus conditions the possibilities of form, not by limiting creativity, but by establishing a space of variation from which forms can be drawn.

The elements of a medium tend to be relatively independent. For example, in a digital image, the color of a single pixel is independent of its neighbors—this independence allows for vast freedom in composition. Similarly, money functions as a medium: payments are loosely coupled and generally independent in denomination, purpose, or context. In programming languages, each character or token can, in principle, appear in many configurations—yet only a subset forms a syntactically valid program (and within this subset, only a few are deemed useful). The obliviousness of the medium to any inherent meaning allows artists to manipulate it freely, opening a space of fiction—of imagined realities, simulations, and myths.

In the medium/form distinction, the form is always more rigid—it asserts structure, order, and direction. However, this assertiveness carries risk: the form may decay, become obsolete, or evolve. This also applies metaphorically to matter: sand adjusts to the shape of a stone, not the other way around. In this sense, form imposes order but remains vulnerable to change.

Luhmann introduces the idea of second-order media: forms can themselves become media for further form. Sound, for instance, is a form produced through the compression of air (the first-order medium), but musical tones—patterns of sound—constitute the medium of music, which then enables the formation of higher-order structures like rhythm, harmony, or composition.

This recursive forming is illustrated in the following SuperCollider code example: (1) A low-frequency impulse is perceived as rhythm. (2) At high frequencies, it becomes a continuous tone. (3) Modulating this tone reintroduces rhythm—thus forming a loop between medium and form depending on the listener’s perception and the system’s configuration.

{Impulse.ar(5)!2}.play

{Impulse.ar(160)!2}.play

{Env.perc().ar(gate:Impulse.ar(1)) * Impulse.ar(160)!2}.play

In music, any tone could, in theory, follow any other—except that the form of the piece imposes constraints. The experience of music as communication arises only for those who can distinguish form from medium—who can recognize not only what is played but what could have been played instead. Musical meaning thus arises from the tension between constraint and possibility—between realized form and the unmarked space of alternatives.

Art establishes rules of inclusion that serves the difference of medium and form as medium. – Niklas Luhmann

This suggests that the difference between medium and form can itself become a medium—a space of released possibility for future differentiations. Art requires rules not to constrain creativity, but to make distinctions legible. These rules are contingent (they could be different) but necessary: they establish a boundary between inside and outside, between form and its other. In Luhmann’s Spencer-Brown–inspired terminology, objects are nothing more than distinctions: a chair is not a thing in itself but a difference drawn and indicated. Thus, indication and differentiation go hand in hand [SB69]. When we name something (a chair, a sound, an image), we do not refer to an object; we enact a form, marking one side and excluding another. Art, in this sense, manipulates forms and mediates between their inclusions and exclusions, continually creating the space for alternative realities.

The art system, like any modern social system, is functionally differentiated—it operates independently from religion, law, politics, or science. It has its own function (to make perception communicable), its own code (art / non-art), and its own symbolic medium (aesthetic experience). But what makes such functional autonomy possible is the capacity for second-order observation: the ability to observe how others observe. Once observers reflect not only on the artwork but on other observations of it, the direct bond between artist, work, and viewer dissolves. You may ask what the artist meant, but you also know that others may interpret the work differently—and they know that you know that they know. This reflexivity transforms art into a self-referential system, sustained by recursive communication: artworks prompt interpretation; interpretations prompt counter-interpretations.

This is where Luhmann deploys the concept of re-entry from Laws of Form [SB69]:

A distinction can be reintroduced into the space it originally divided.

Communication about art becomes a form of art, and vice versa. The system observes itself and thus perpetuates its evolution. Importantly, this recursion doesn’t demand “truth” or stable meaning. All it requires is that communication continues.

In line with information theory [Sha48], a communication event must involve contingency: the receiver must be able to ask why this and not something else? The same applies to art. An artwork must be surprising, not arbitrary. It must be contingent—other arrangements were possible—and yet compelling in its current form. If an artwork has no form, no differentiation, no surprise—then nothing is communicated.

This logic applies not only to artworks but to the system of art itself. The system can mock itself, recode its own distinctions, or dissolve forms back into mediums. At this point, form becomes a commentary on form—art that exposes its own contingency. This is risky. Without enough loose coupling—without room for difference—the system collapses into tautology. Yet when done successfully, the form demonstrates that it could also be a medium, offering possibilities for recombination, reinterpretation, or historical transformation.

Luhmann ultimately defines the artwork as a communication of order—not in the sense of transmitting the world’s structure, but in constructing an alternative version of reality. The artwork fixes possibilities—it marks one side of the form—but in doing so it points to the unmarked space, the realm of what could have been. This concept derives from Spencer-Brown’s notion of distinction:

To distinguish is to mark a space and, in doing so, create its other and a boundary.

The beginning of an artwork is such a distinction—it opens up form by crossing from the unmarked into the marked. The subsequent development of the work must maintain internal coherence: what follows must “fit,” not logically, but aesthetically. If something feels out of place, we register it as a disturbance—an error in the logic of the form. As Luhmann writes:

The specificity of art forms is based on the fact that the determination of one side does not leave open what can happen on the other side. It does not determine it fully, but it removes it from whimsy. – Luhmann [Luh97]

Code as Form#

A computer program can be understood as a structured form, composed within the medium of a programming language. As a collection of operations with a specific syntax and semantics, code functions much like a formalized artwork—it creates order out of the open combinatorial space that the language makes possible.

From a humanistic standpoint, programming languages are often seen as precise instruments of expression. Unlike natural languages, they are designed to be unambiguous: a syntactic error leads to a failed compilation or abrupt termination. From this rigidity, programmers often extrapolate a broader epistemological claim—that if a system can be implemented, it must be understood.

The reasoning proceeds as follows:

Major premise: Programming languages are unambiguous.

Implication: A valid program yields a deterministic behavior.

Implication: To write a correct program, one must know what result is desired.

Conclusion: The implementation proves the clarity of thought.

While it is true that programming requires syntactic precision, the belief that programs reflect fully formed, pre-existing ideas is a myth. Programming is not simply the transcription of thought into code. Rather, it is a process of contingent selection within the medium of code, constrained by its grammar and toolsets.

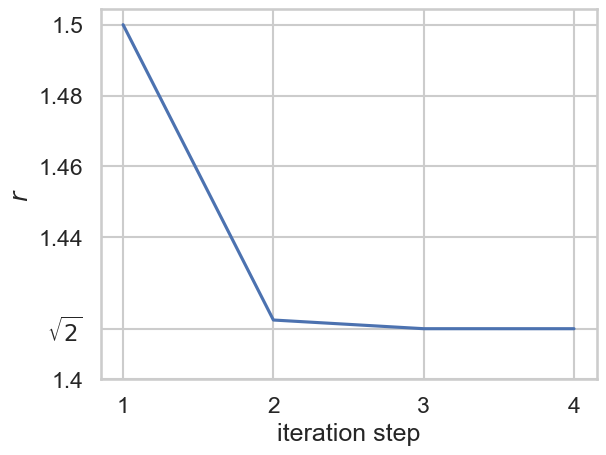

Consider the following example—a Newton-Raphson algorithm to approximate \(\sqrt{2}\). The code is formally correct, but without interpretation, its meaning is not apparent.

Algorithm 1 (Newton’s Algorithm to Approximate \(\sqrt{2}\))

Output Approximation of \(\sqrt{2}\)

\(x \leftarrow 2\)

\(r \leftarrow 1\)

\(v \leftarrow 1\)

While \(|v| > 0.001\)

\(m \leftarrow x / r\)

\(t \leftarrow r + m\)

\(r \leftarrow t / 2\)

\(u \leftarrow r^2\)

\(v \leftarrow x - u\)

return \(r\)

Can we unravel the mystery hidden behind the complexity of these statements? We can see that if \(x\) and \(u\) are similar, the computatation stops. Since \(u \leftarrow r^2\) and \(x = 2\) the computation stops when \(r\) is close to \(\sqrt{2}\).

How is \(r\) computed? Well, if we substitude all the variables we get

and since \(x = 2\), we get

Substituting \(r\) for \(\sqrt{2}\) gives us

Therefore, if \(r\) would be exactly \(\sqrt{2}\) (which is impossible since it is a irrational number) then \(r\) would not change.

Let’s say \(r = (\sqrt{2} \pm \epsilon)\) then we get

We know that for small \(\epsilon\) the sum is close to \(2\sqrt{2}\) and each of the summands is close to \(0.5\sqrt{2}\). From the formula we can see that the first summand is about \(\epsilon\) larger or smaller than \(\sqrt{2}\). So what about the second summand? Clearly it is the opposite, i.e., if \(\epsilon > 0\) the second summand is smaller than \(\sqrt{2}\).

If \(r = \sqrt{2} + \epsilon\), we want \(r\) to go down thus

should hold. This follows from the following inequation:

On the other hand, if \(r = \sqrt{2} - \epsilon\), we want the opposite, thus

should hold. This follows from the following inequation, which holds for \(\epsilon < 2\sqrt{2}\):

If we look at the starting value for \(r\) and all the operations, we can clearly see that \(r\) will never be negative thus \(\epsilon < 2\sqrt{2}\) holds for the execution of the algorithm.

We did a lot of work and thinking to analyse Newton’s algorithm. In the end we figured out that \(r\) approches \(\sqrt{2}\). We still don’t know how fast \(r\) converges towards \(\sqrt{2}\). We also did not look at possible numerical pitfalls—after all computers are not that good at dealing with the infinite. It is likely that Newton started with mathematical equations before writing down the statements of advice. If we just implement the steps without a proper analysis we do not really understand what is going on and simply looking at the algorithm does not help either.

These kind of algorithms echo the humanistic perspective: Humans are in total control by advicing the computer precisely what commands it should execute.

The form is the written down algorithm in a specific language (medium), e.g. sclang—the SuperCollider programming language.

(

x = 2;

r = 1;

v = 1000;

while({abs(v) > 0.001},

{

m = x / r;

t = r + m;

r = t / 2;

u = r * r;

v = x - u;

});

r.postln; // 1.4142156862745

)

Fig. 1 The value \(r\) converges towards \(\sqrt{2}\).#

However, from a systems-theoretical perspective, the code is the form, and the programming language is the medium—a space of loosely coupled syntactic elements. The language makes many configurations possible but enforces strict rules on what counts as valid. Thus, the rigidity of the medium enables the specificity of form. Moreover, programming is rarely an act of isolated genius. It is embedded in a network of observers: documentation, standards, libraries, online forums, other programmers. Every function or library call is a communication, stabilized over time and selected again in the present. The programmer does not create ex nihilo but operates within an autopoietic environment of existing selections.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT may generate Python code that solves a given task, but this does not imply understanding—not in a Luhmannian sense. It merely recodes existing selections, much like a novice programmer might copy and adapt from Stack Overflow. This recursive copying is structurally similar to how communication reproduces itself: what matters is not subjective insight, but systemic continuation.

Programming, like art, is not (subjective) expression but selection within a medium.

The intelligence of a programming language lies not in its semantics but in its symbolic generalization—it exceeds the diversity of things and permits consistent differentiation. Like Luhmann’s notion of form, code reduces complexity: it constrains the space of what can be done next, rendering the continuation meaningful. In this light, we can reconsider code as form in the Luhmannian sense:

A program is a contingent realization drawn from the medium of a language.

Its execution is a function of selections, not expressions of subjective will.

Understanding is not given but constructed within communication—through second-order observation, testing, debugging, documentation, and dialogue with other observers.

Thus, programming becomes not a mirror of clarity, but a field of systemic observation, rich in contingency, historicity, and structural constraints. And like all forms within social systems, its success lies not in its internal elegance, but in its capacity to make sense (an act of psychic and social systems) under the condition of having been otherwise.

Artistic Coding#

In the realm of artistic or creative coding, the perception of programming as a purely rigorous and deterministic activity dissolves. Here, code functions less like a set of instructions and more like a musical instrument—an interface for improvisation, exploration, and perceptual experimentation. Artists working with frameworks like p5.js, Processing or nannou rarely begin with a fully formed idea to transcribe into code. Instead, they start with something minimal: a loop, a shape, a rule, a chance operation—and build iteratively. They run the program, observe what emerges, and adjust parameters in response to what appears. This back-and-forth defines a process that is not linear or goal-driven, but contingent and open-ended.

The artist does not impose a vision onto the medium, but participates in bringing forth a form—selecting from a horizon of possibilities conditioned by the language, the libraries, and the current state of the evolving work.

In this way, artistic coding aligns with Luhmann’s idea of form selection: what comes next is determined not by expressive will, but by the constraints and affordances of the medium, coupled with historical decisions (what has already been drawn, coded, heard).

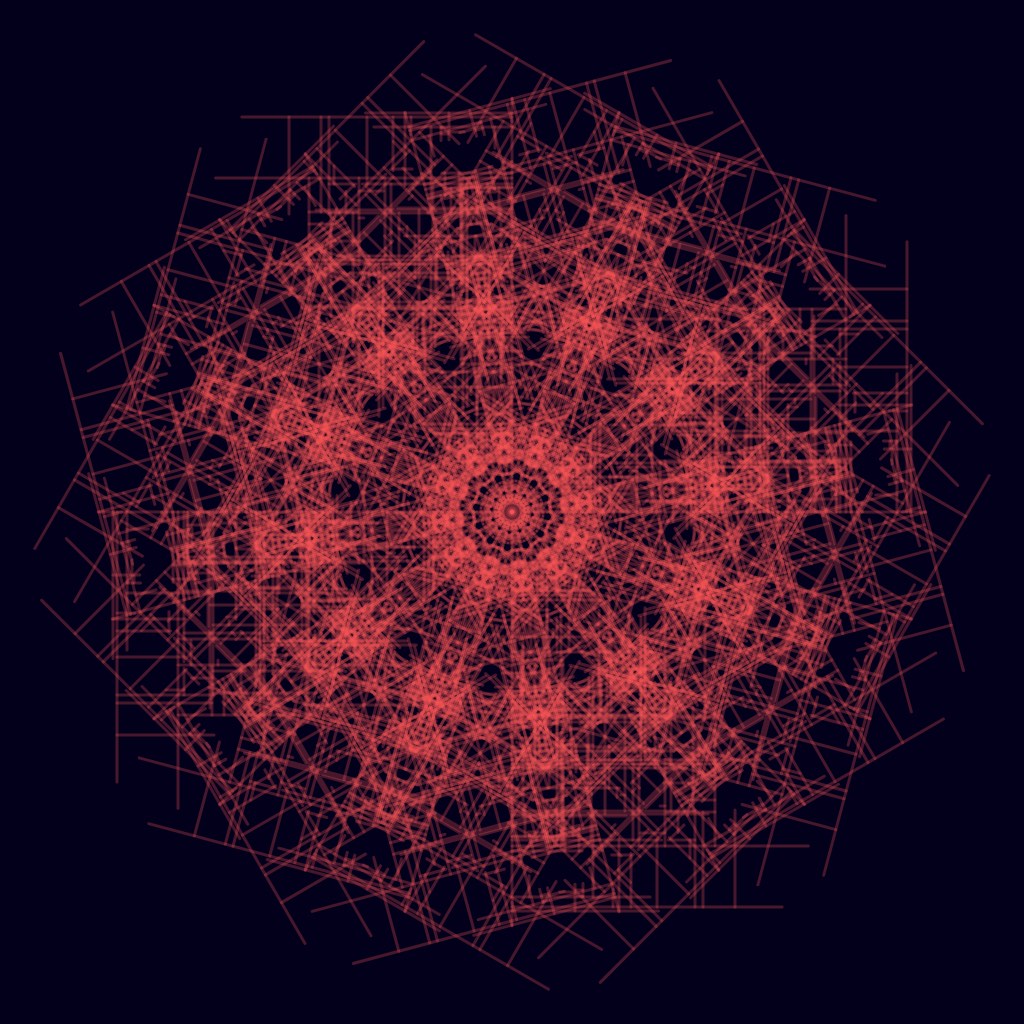

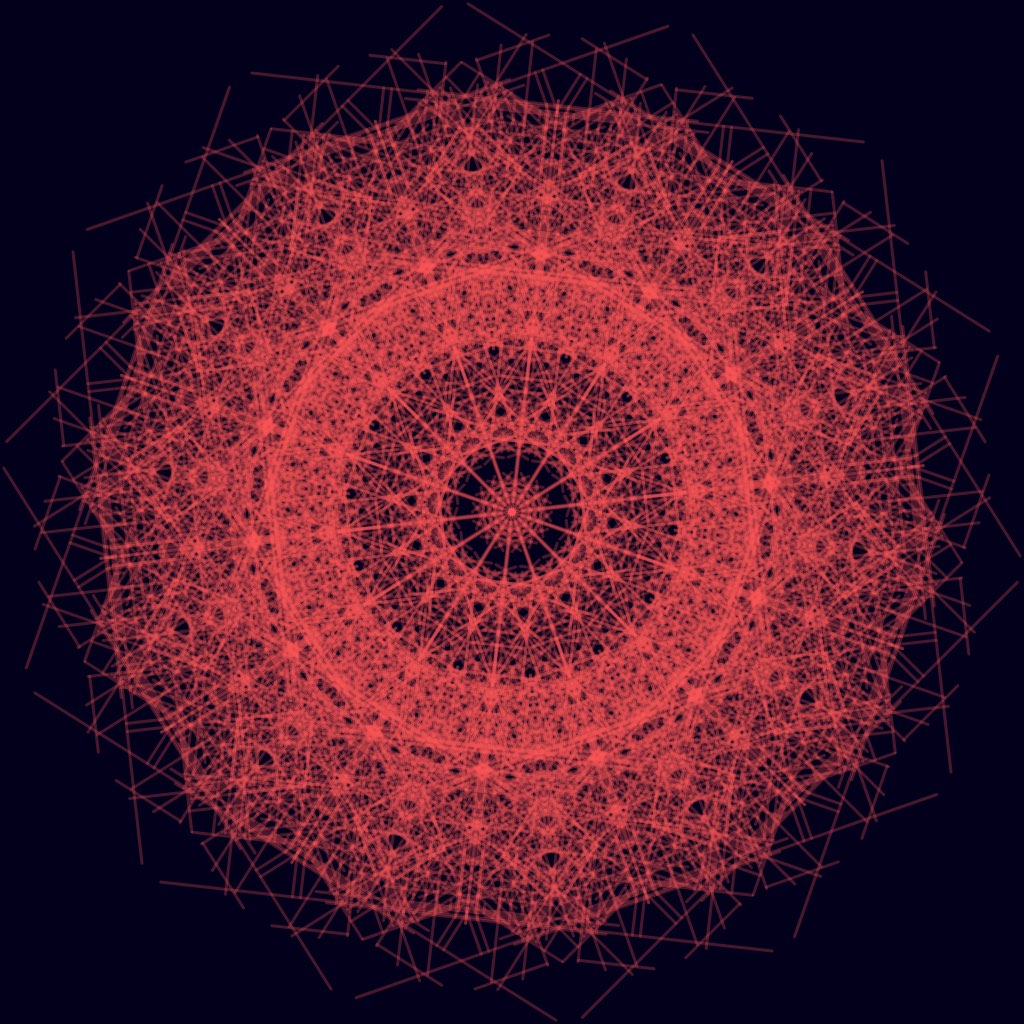

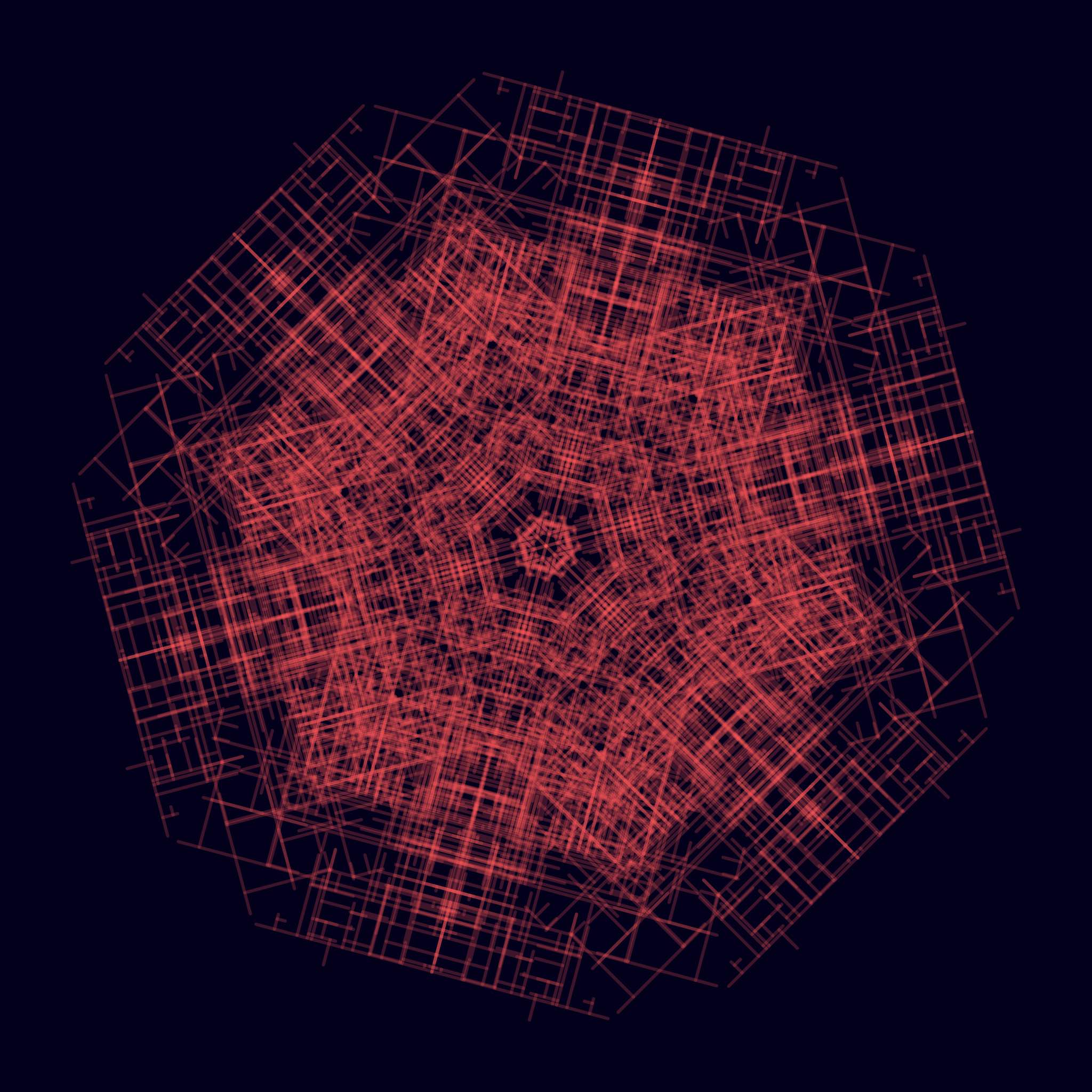

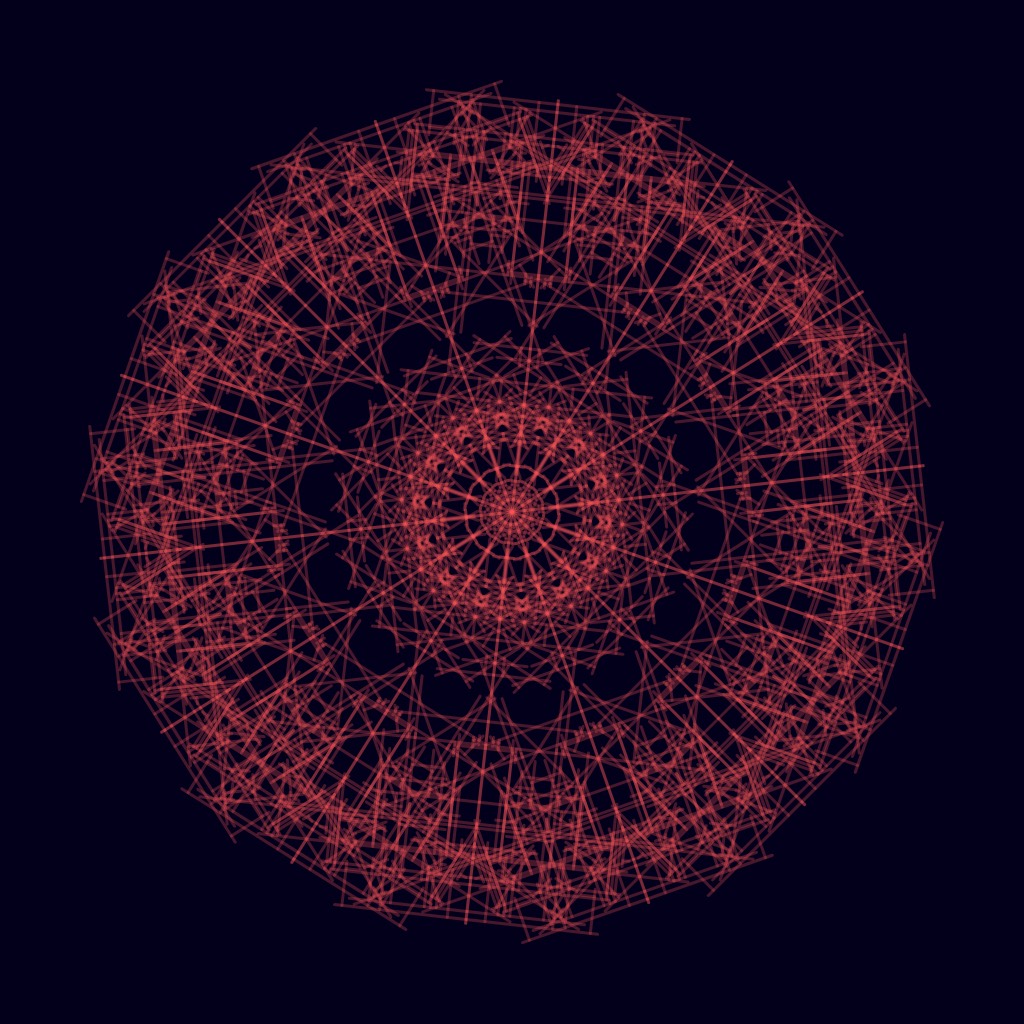

For me, the appeal of generative art (by which I exclude AI generated art) lies in the exploration of simple rules and the emergent complexity they produce. In one project, I constrained myself to draw only perpendicular lines. Each line could spawn child lines at its endpoint, with a certain probability, and each child had to be perpendicular to its parent. Both parents and children could continue spawning new lines. The resulting structure was then mirrored around a circle, creating a radial symmetry.

In such work, the form emerges from a dance between randomness and recursion, discipline and disruption—a recursive coding of possibility within a symbolic medium.

The same logic applies in the acoustic domain—particularly in live programming (e.g., in SuperCollider or TidalCycles), where code is written and executed in real time as part of a musical performance. One of the most fascinating features of live coding is that it exposes the process. When something goes wrong—a glitch, a syntax error, a crash—the illusion of seamless performance collapses. Suddenly, the medium reveals itself: the medium hidden behind its functioning form becomes visible and the artist can be observed as a struggling resistence against failure.

Here, the difference between form and medium becomes palpable.

The glitch, in this context, is not simply a failure but a disruption of the system’s expectations—a moment where the coupling fails and the artwork becomes reflexively aware of its own construction. In Luhmannian terms, the form exposes its contingency and the system observes its own operation. The performance does not merely present music, but stages the second-order observation of music-making itself.

Creative coding thus operates in a space where artist, code, medium, and audience all participate in a network of recursive observation. The form is not static; it is evolving, contingent, and communicatively active—a selection that constantly reintroduces its own difference.